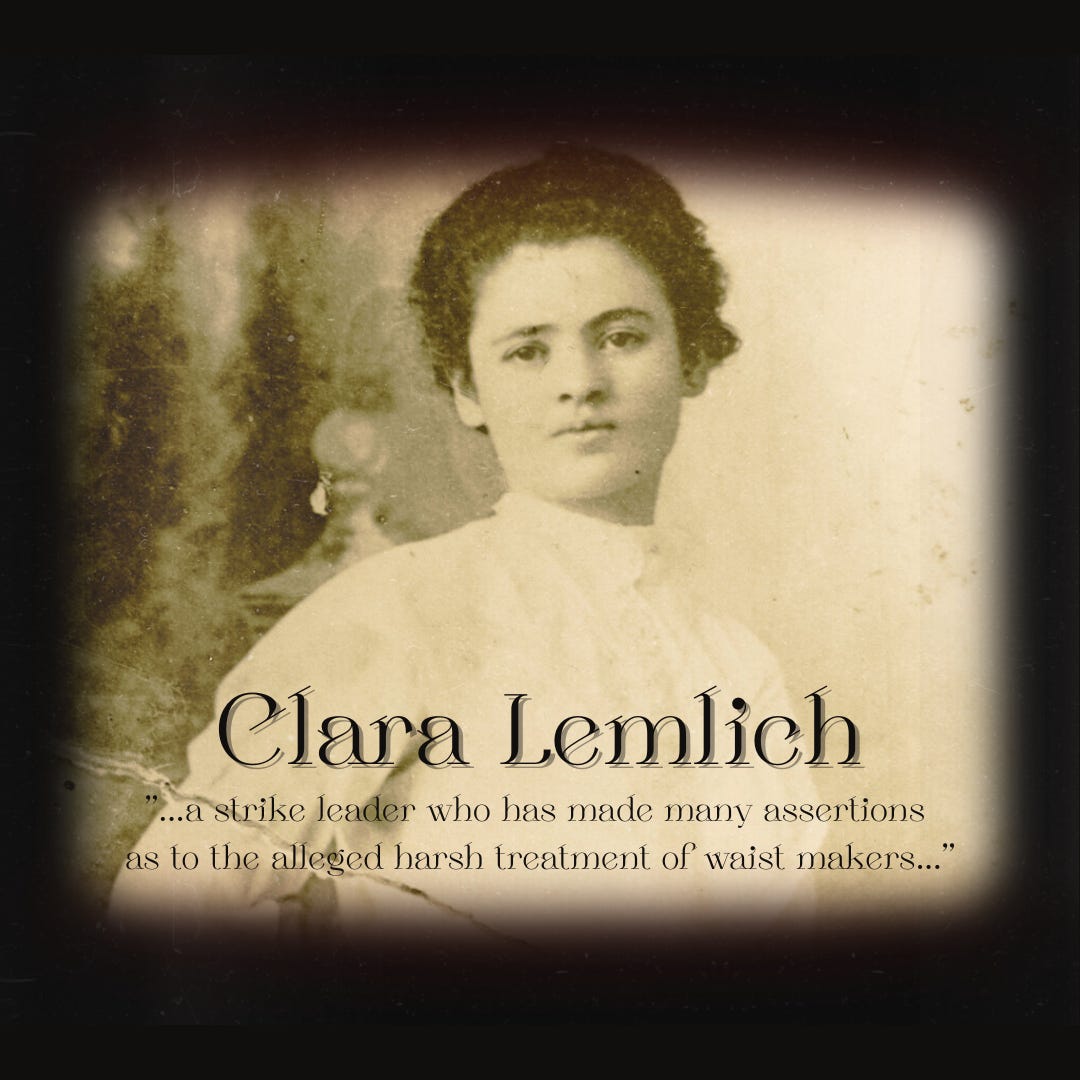

Clara Lemlich

"...a strike leader who has made many assertions as to the alleged harsh treatment of waist makers..."

On 2 November 1909, 23-year-old Clara Lemlich stood before the anxious and agitated members of New York City's Cooper Union. Still bruised from her attack by thugs hired by union breakers and speaking in her native Yiddish, she marched to the front of the hall and said, "I am one of those who suffers from the abuses described here, and I move that we go out on a general strike — now."

And so began the garment strike known as "The Uprising of 20,000."

The Ukraine and Pogroms

Born on 28 March 1886 in Gorodok, Ukraine, Clara Lemlich grew up in an impoverished Jewish family. Like many others, the Lemlichs primarily spoke Yiddish at home. Also, like many other Jewish families living in the Ukraine at this time, Clara's family frowned upon the idea of her learning Russian or educating herself—but Clara did it anyway.

She used her skills as a seamstress and her ability to read to earn money. With that money, she bought books and pamphlets to educate herself about the world around her. This is how she came to read the Communist Manifesto by Carl Marx, the book that led her on her Socialist path.

Clara Lemlich, like so many others, was a Jewish family living during a time of increasing anti-Semitic violence under the Russian monarchy. Tsar Alexander III, like the Tsars before him, implemented policies that marginalized the Jewish population. One example is the May Laws of 1882, also known as The Temporary Regulations Regarding the Jews. The May Laws imposed living and working restrictions on Jews in the Russian Empire. These laws further restricted their rights and movement, and they fostered an increase in pogroms—violent riots aimed at Jewish populations that were really nothing more than organized massacres.

The pogroms were often incited by persons who blamed the Jewish population for the hardships faced by the Russian people that were entirely out of the Jewish population's control. Most attacks were incited by false accusations or fabricated rumors fueled by local newspapers.

Plus, it didn't help that there was a lack of government intervention to protect Jewish communities. This silence further exacerbated the violence, forcing thousands of Eastern European Jews to flee their homes and move to North America.

It was after the devastating Kishinev pogrom in 1903, which claimed the lives of around 50 Jews and left close to 500 injured and homeless, that the Lemlich family decided to immigrate to the United States.

Clara Lemlich was 16 years old.

Clara and her family arrived at Ellis Island and lived in one of the many tenement buildings on the lower East Side. Within a few weeks of arriving, she had found a job at a garment factory.

Labor Activism and the Uprising of the 20,000

In New York City, Lemlich joined thousands of immigrant women working in garment factories under grueling conditions—12-hour days, six days a week, for as little as $3 per week. Within two years of living in the tenements and working in one of the many sweatshops that dotted New York City, Clara was outraged by these exploitative practices. She, like so many others at this time, embraced the wave of socialism and communism sweeping through the working class and decided that she wanted to make a difference. A proponent of unions and livable wages, shorter working hours, and better working conditions, Clara chose to take a stand. These beliefs led her to become a member of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU). Before long, through her speeches and leadership skills, she quickly rose to prominence in the organization.

Before that day in November of 1909, there had been other walkouts and strikes. The work life of a garment worker was grueling at best. With long hours that ran six days a week, most workers in factories like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory worked in dark and dirty conditions with low light and only one short break a day. During the day, the exits were locked to ensure workers didn't attempt to leave early, and at the end of their shifts, they were often searched to ensure they were not stealing from their employers. Plus, while young women and girls made up most of the workforce, they were rarely protected and were subjected to sexual and verbal harassment at their jobs.

In the late summer of 1909, Clara was picketing at Louis Leiserson's garment factory, where she worked as a draper. By this time, she was known for advocating Unions and her loud desire for change. She had led other notable strikes, one in 1907 at Weisen & Goldstein's waist shop and another at the Gotham waist factory in 1908. By the time she walked the line at the Louis Liserson's strike, she was seen as a nuisance by factory owners and their friends at the "political factory" known as Tammany Hall. So, on 10 September 1909, after leaving the garment factory and the strike line, Clara walked towards the Lower East Side; she met up with a group of strikebreakers. Two of the men, Lawrence Ferrone, a.k.a. Charlie Rose, a twice-convicted burglar who was also okay with doing most things as long as there was money to be made, and Charlie's friend, William Lustig, a prizefighter, and a bare-knuckle boxer, would take the lead.

Clara would have recognized the men as the strikebreakers hired by factory owners to "protect their interests." She would have known their faces as they beat her, leaving her on the sidewalk, bloodied and with two broken ribs.

But this would not stop Clara.

A little more than ten weeks later, she stood in Cooper Union and said:

“I have listened to all the speakers, and I have no further patience for talk. I am a working girl, one of those striking against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in generalities. What we are here for is to decide whether or not to strike.

I am one of those who suffers from the abuses described here, and I move that we go out on a general strike — now.”

And will you keep the faith? Will you swear by the old Jewish oath of our fathers?

Her words galvanized thousands of garment workers into action. The Uprising of the 20,000 lasted two months and included the support of socialites like Ann Morgan (J.P. Morgan’s daughter) and suffragist Alva Belmont. In the end, while all of the Union’s demands were not met, the Uprising did secure significant concessions from factory owners, including higher wages and shorter hours.

Like Emma Goldman and possibly Hanny Schaft,1 Clara Lemlech’s dedication to social justice came at great personal cost. After her involvement in so many strikes, she was blacklisted from garment factories and monitored by government agencies during the Red Scare due to her involvement with the Communist Party.

Love this post? Give it a heart and restack!!

Lasting Legacy

Ten years after the 20,000 Uprising, Clara Lemlich was interviewed, and she said that she had fire her mouth. “What did I know about trade unionism?” she said. “Audacity–that was all I had. Audacity.”

She was correct in her statement. If there are two things that exemplify her life, they are audacity and perseverance. From leading one of the largest strikes by women workers to advocating for broader societal reforms, she left an indelible mark on labor rights and feminist movements. In 2010. LaborArts, a nonprofit that “... presents powerful images to further understanding of the past and present lives of working people. Our events and contests expand on this effort,” began awarding the Clara Lemlich Awards each year. The awards for social activism “celebrate the lives of incredible women whose many decades of brilliant activism have made real and lasting change in the world.”

Learning about Clara Lemlich’s life reminded me that change often begins with the courage to speak out—no matter how daunting the odds or how difficult it feels.

Did you miss:

Graveyard Gossip: April

This monument, found in the Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California, is dedicated to Lillian Leitzel (Cadona), a world-renowned acrobat who performed with her mother, Nellie Pelikan, and the…

Monthly Newsletter!

The Branch that Time Forgot

When you spend hours researching other people's family histories, you begin to wonder, "Why have I not found interesting stories in my family tree? "The simple answer is that you're not spending enough time on your own research. Hence, you don't know as much about your family as you do your clients'.

Part two of my own going Family History discovery journey. Read the first installment here! Part three coming soon.

HOW TO RESEARCH YOUR ANCESTORS:

Is is possible your ancestor took part in the Uprising of 20,000? Well, here are some places to look for their names and to learn more (and more in depth) about the Garment Strikes.

The National Park Services: It may sound weird, but the NPS is an amazing genealogy resource. It’s online an free as well. If you’re already using it to research Civil War Records, just know, they offer even more than that. They have a boastful collection of records and articles worth checking out. If you head HERE you will find their Family History Landing Page, which is a great place to start.

Library of Congress: Garment & Textile Unions Guide: The Library of Congress has SO MUCH to offer, both online and in person. The featured link (above) will take you to learn more about the unions that were specifically for garment and textile workers. This one RIGHT HERE talks about Labor Unions as a whole, since the 19th century to today.

Jewish Women’s Archive: While all garment workers weren’t Jewish, people like Clara Lemlich was. This resource offers a lot of information about the strikes and it also has a long bibliography with additional books and articles available to learn more about the strikes.

New York City Arrest Records: Clara Lemlich was arrested 17 times for striking. That’s 17 arrest records out there. The New York State Archives has these holdings. They also have a searchable websites and a knowledgeable staff who can help you locate the information not online.

Society of American Activists: This site has labor archives for both the United States and Canada.

and don’t forget Newspapers! Labor strikes were reported and your ancestors name may have ended up in the paper. Sites like Chronicling America and Perdue Library Research Guides grant access to online news archives, available with an internet connection.

Don’t forget to give this post a heart and share it with a friend!

To learn more about Genealogy by Aryn - head over to GenealogybyAryn.com, stop by and say hello on Bluesky - Instagram - Facebook - YouTube

Be sure to check out my Etsy Shop and stop by my Genealogy Shop.

Looking to learn more about writing your family history? Check out From Research to Novel!

For more information about my Genealogical Services visit GenealogyByAryn.com or email me at aryn.genealogy@gmail.com. For more information on Writing Services - visit ASYounglesAuthor.com

I didn’t write about the rumors she was executed for her communist beliefs, but it is a standing rumor. Poldermans, Sophie, and Gallagher Translations. Seducing and Killing Nazis : Hannie, Truus and Freddie: Dutch Resistance Heroines of WWII. Haarlem, Sww Press, Sophie’s Women Of War, 2019.

it's always inspiring to hear how one person can make a difference...

Fascinating story and such incredible research to learn about these unknown heroes in our history.