The Story of Eliza "Lyda" Burton Conley

AKA - Researching your First Nation Ancestry & how fighting for your heritage with fearlessness and strength can move mountains and save cemeteries.

Imagine a fearless Native American woman who, decades before women could vote, stood shotgun in hand to protect her ancestors' sacred burial ground—challenging the U.S. government, becoming the first Native American woman to argue before the Supreme Court, and ultimately saving a two-acre cemetery from developers who saw only prime real estate where she saw the hallowed ground of her ancestors.

This week, let’s explore the extraordinary story of Lyda Conley: lawyer, guardian, and unyielding defender of her people's heritage.

To honor Native American Heritage Month, I would like to introduce Eliza “Lyda” Burton Conley, who lived in both the European/American and First Nations worlds. As she grew up and began to understand the world, she used her energy and time to protect her ancestors, the Wyandotte Nation.

To understand Lyda Conley, first we must learn about the Wyandotte.

Who are the Wyandotte?

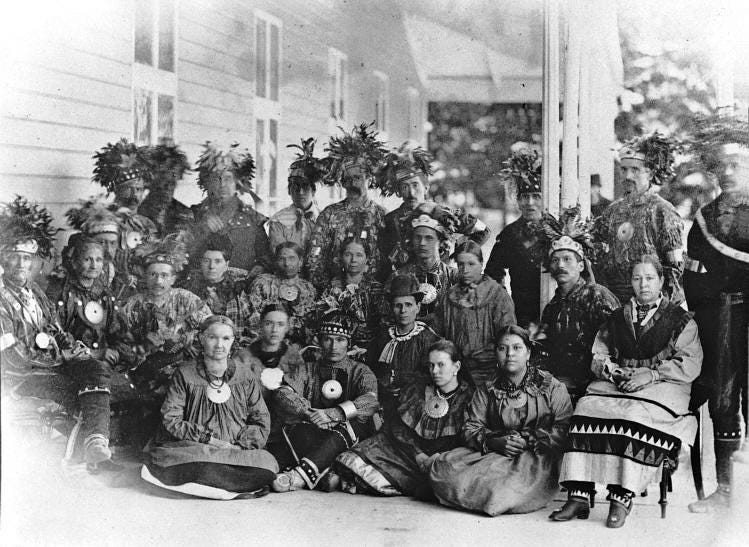

The Wyandotte Nation, or the Wendat people, emerged in the mid-1600s from the union of the Attignawantan, Wenrohronon, and Tionontati Nations after they were defeated by the Iroquois Confederacy.

Originally inhabiting the Great Lakes region, particularly in modern day Ontario, Canada, the Wendat were skilled agriculturalists and traders, which is how they first encountered the French colonists — it is also they were renamed the more popular name American’s know them by: The Huron. It was the French settlers who dubbed them Huron. The French referred to the Wendat people as “hure,” meaning, “boar’s head” because of the distinct hairstyle the Wendat people wore. [NOTE: hure can also be translated to rough or boorish.] Over time, “hure” transformed into Huron, for which the great lake was named.

The Wyandotte developed a sophisticated society based on a matrilineal clan system. Their communities were led by civil and war chiefs, with women holding significant political power, particularly in selecting chiefs and important decision-making processes. The nation was also known for its expertise in diplomacy, earning them the title "Keepers of the Council Fire" within the Council of Three Fires alliance.

The 17th and 18th centuries brought changes to Wyandotte society. The European contact introduced both new trading opportunities, but also, devastating diseases, like smallpox. Plus, conflicts with the Iroquois Confederacy forced many Wyandotte to relocate, leading to a series of migrations southward through Michigan, Ohio, and Kansas. Despite these challenges, the nation worked hard to maintained its cultural identity and political influence, often serving as a mediator between other Indigenous nations and European powers.

Finally, after various treaties that reduced their landholdings, the Wyandotte were forcibly relocated to Kansas and later to Oklahoma due to the U.S. Indian Removal Act. This is where our story begins:

Lyda Conley, birth name Eliza Burton Conley, was born around 1868 in Kansas, where the Wyandotte were forced to move in 1843. She was the daughter of Eliza Burton Zane, the daughter of Issac Zane and White Crane (White Crane was the daughter of Wyandotte Chief Tarhe), and Andrew Syrenus Conley, a second-generation American farmer born in Connecticut who had immigrated to Ohio, where he met and married Eliza Burton Zane.

Like many other multicultural Wyandotte families, the Conley moved west with the tribe to remain a united community.

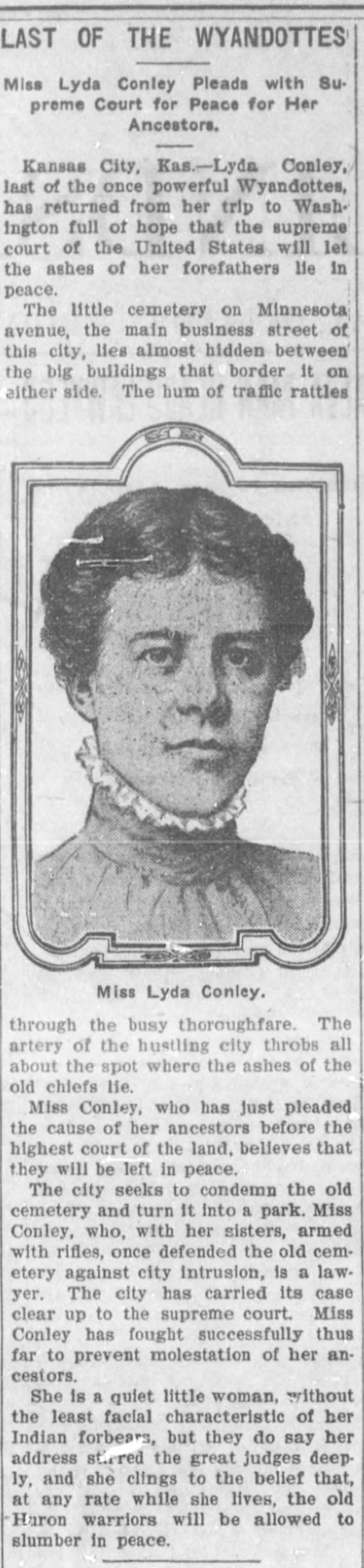

Lyda was the youngest of four sisters, all of whom were encouraged to be educated and independent of their own minds, much like the matrilineal Wyandotte beliefs. So it was no surprise that Lyda became the first woman to be admitted to the Kansas Bar Association and, later, the first Native woman to be admitted to argue in front of the U.S. Supreme Court.1

While the Wyandotte were accepting of Europeans, like Lyda’s father, into their society, this did little to change the backdrop of systemic discrimination and manifest destiny, Lyda Conley and others faced in the United States. Regardless, she choose to stand by her principles and defend her family heritage when she faced the U.S. legal system to stop the desecration of her people's sacred lands in Kansas City, Kansas.

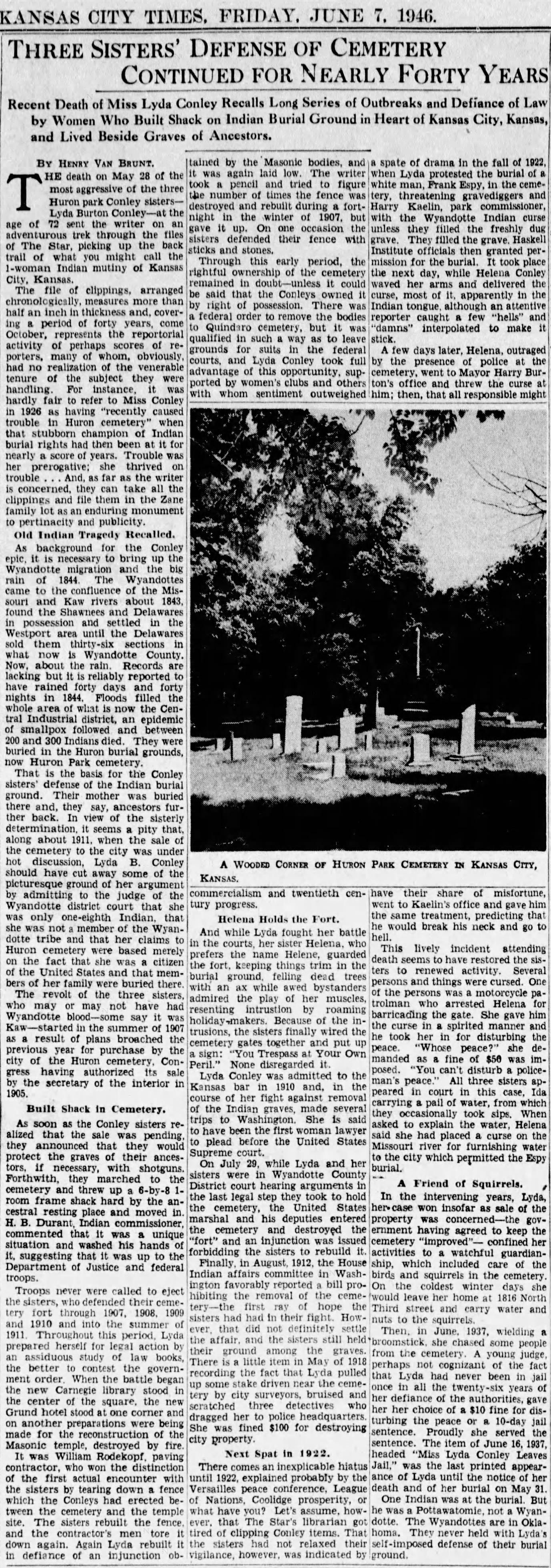

This fight began when her tribe's cemetery, known as the Huron Indian Cemetery, was threatened with development, prompting her to take direct action by building a caretaker's lodge on the property and physically guarding it with her sisters.

The fight between the Wyandotte and the United Stated began in 1899 when real estate speculators approached the Wyandotte with intent to purchase the land. The meeting was met with with protest, and the sale was not completed — but the speculators weren’t about to give up.

By June 1906, when the men who wanted the land were tired of not getting what they wanted, the buried in section of a 65 page Congressional appropriations bill was the authorities for the Secretary of the Interior to sell a tract of land located in Kansas City Kansas. Enter the Conley sister: Lyda, Ida, and Helena.2

The Conley sisters built “Fort Conley” inside the cemetery to protect the graves of their parents and ancestors. By October of 1906, Lyda was quoted as saying, “In this cemetery are buried one-hundred of our ancestors…why should we not be proud of our ancestors and protect their graves? We shall do it, and woe be to the man that first attempts to steal a body. We are part owners of the ground and have the right under the law to keep off trespassers, the right a man has to shoot a burglar who enters his home.” in the Kansas City Time.

J.B. Durant, the Chairman of the Government Commission pushed forward with the sale. 3

By 1909, Lyda's persistence and strong spirit, combined with the support of her sisters and community, she did what no other indigenous woman had managed to do in the 133 year history of the United States of America. She became the first Native American, and the third woman, to argue a case before the United States Supreme Court.

The Case of Conley v. Ballinger

The case of Conley v. Ballinger4 was pivotal in the Conley Sister's crusade to protect the Huron Indian Cemetery.

Lyda graduated Law School and was admitted to the Missouri Bar in 1902. Using that experience and knowledge, she stepped into the legal arena, determined to halt the desecration of her ancestral land. Conley argued that the federal government could not sell the Wyandotte Nation's Huron Indian Cemetery in Kansas City, Kansas, because of a treaty the U.S. signed with the tribe in 1855.

By 1910, with their case being heard by the United States Supreme Court, the justices ruled in favor of the government, allowing the land sale. More real estate moguls moved forward, making offers on the land — but Lyda and her sister were not about to give up their fight. They continued to guard the cemetery.

In 1913, Kansas state Senator Charles Curtis visited the Huron Indian Cemetery and once he returned home, he passed a law to protect it from development.

The initial ruling reflected the broader systemic challenges faced by Native Americans during this period, where the legal landscape was heavily skewed against minority groups and marginalized communities – which can still be felt today. But the tale of Lyda Conley and her sister — Ida and Helena — also show how perseverance can pay off.

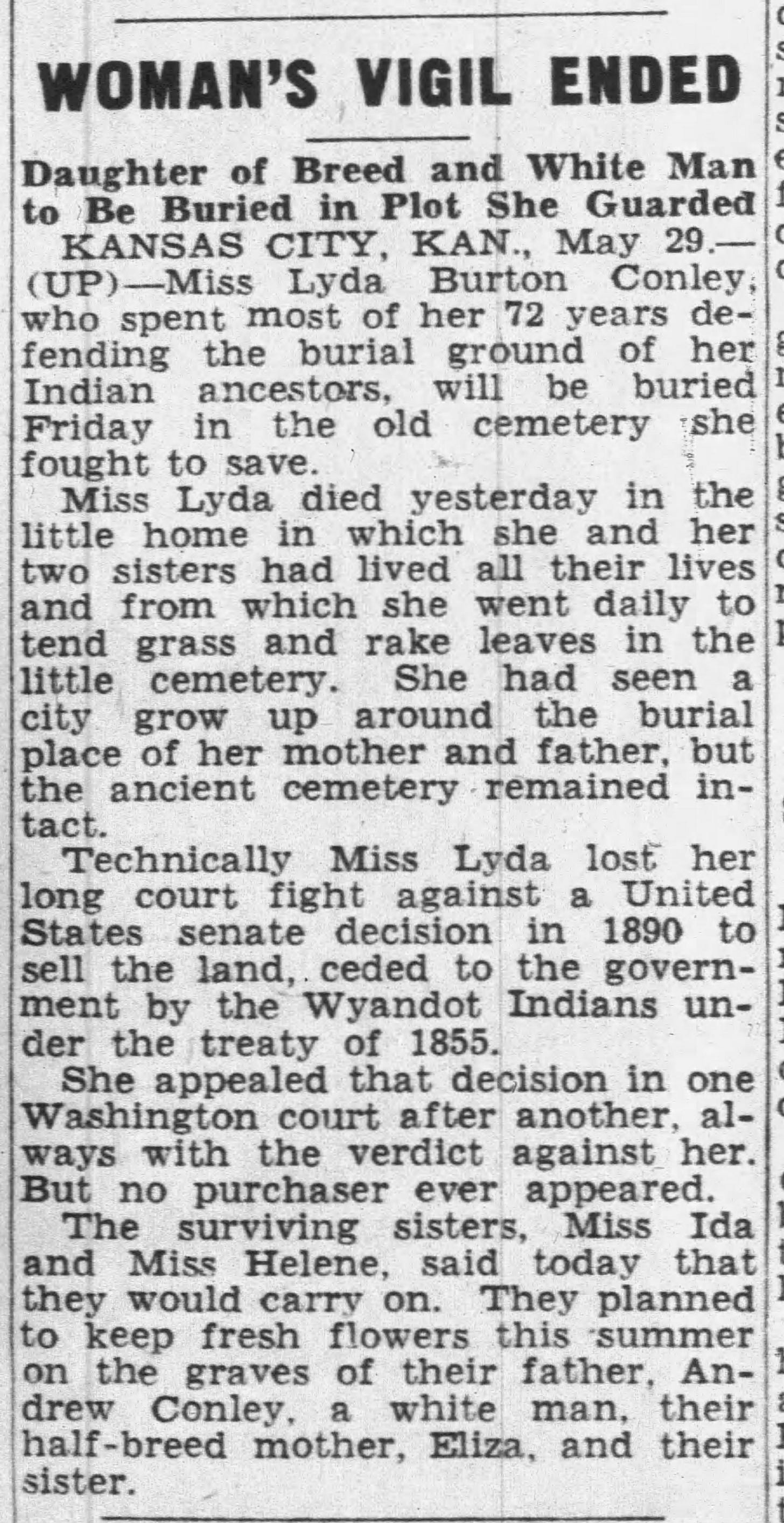

Although Lyda Conley did not achieve a legal victory in her lifetime, her fearlessness inspired generations and laid the groundwork for future victories in Indigenous rights.

Lyda Conley's legacy resonates in contemporary movements like protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline (the Standing Rock Protest), Missing and advocacy for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), and other Nations seeking to protect sacred sites and ancestral lands from modern threats.

Conley's story reminds us of the importance of vigilance and activism in safeguarding cultural heritage. In recognition of her contributions, the Huron Indian Cemetery, renamed the Wyandotte National Burying Ground, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2017.

This designation helps preserve the site and ensures that the memory of Conley's struggle and the broader fight for Indigenous rights remain alive in the public consciousness. Her fight also shows some alternative avenues to researching one's ancestral heritage concerning First Nation ancestry.

Lyda Conley’s Life & Death:

Lyda Conley never married. She remained in the home her family had owned since her childhood, living out the remainder of her modest life in poverty. The remainder of her life was dedicated to using her legal expertise to help other Native Americans receive the legal representation they deserved and remaining close to her family and community.

After almost forty years of fighting to preserve the Wyandotte National Burying Ground, on May 28, 1946, 72-year-old Lyda Burton Conley was leaving Kansas City Public Library, where she was struck in the head by a brick in a mugging attempt. Lyda died a day later in the house she and her sisters had been raised in, and later, she was buried next to her parents in the burying ground she fought so hard to protect.

She only had $.20 in her purse.

With family history research, the core of resources in America tends to fall under the theme of Americans of European descent.

This is important to know and understand when you begin researching your First Nation roots. While you may be able to easily find some information, building out a full tree will be met with many challenges along the way, from incomplete records mixed with a lack of historical effort and a dash of concealed identities (because people were just trying to survive) to a lack of resources needed to map out your Indigenous heritage accurately.

Still, it is equally important to recognize that some documents exist and that with each discovery we locate and document, we lay the groundwork for the next generation of genealogists to build on those findings. So, do not give up if this is your path. Remember, our nation was shaped not only by those of European descent; its identity existed long before the English or French set foot on this land. America was born in the communities of our American Indigenous Nations brothers, sisters, neighbors, and friends.

Researching Alternatives:

While many online databases may not have the information you are hoping to find, here are some alternatives that helped me learn more about Lyda Conley.

Newspapers.com (Chronicling America is a great, and free, alternative. Also be sure to check what resources your local library offer for newspaper searches)

Other notable sites to check out:

Searching for new and different resources outside the commonly marketed sites is the first place to locate online and digitized archives and resources that will help you build your non-European family tree. Still, it is also important to understand, not all information is digitized. Family history research can be time consuming but it is also rewarding, making it worth the time to contact repositories in the areas your ancestors lived.

To learn more about about Genealogy by Aryn - head over to GenealogybyAryn.com, stop by and say hi on BlueSky - TikTok - Instagram - Facebook

Searching for Genealogy or Family History Gifts? Check out my Etsy Shop and stop by my Genealogy Shop.

Dean, Samantha Rae. “‘as Long as Grass Grows and Water Flows’: Lyda Conley and the Huron Indian Cemetery.” FHSU Scholars Repository, 2016. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/31/.

The oldest Conely sister, Sarah “Sallie”, died in her twenties. I was unable to locate much information about Sarah “Sallie” outside of the 1875 Kansas State Census.

For the full Timeline of the Huron Indian Cemetery drama - visit: Wyandot.org

“Conley v. Ballinger, 216 U.S. 84 (1910).” Justia Law, 2024, supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/216/84/. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024.

Fantastic article! Very well written and thank you for including resources for those who might be new to this type of research. Looking forward to more of your posts.

LOVE This! Terrific examples of resources that are out there and I admire that you've provided them. Personally, I'm looking for more like this.