Emma Goldman and the Palmer Raids

aka - How to Get Kicked out of America: a Radical's Guide to Deportation

As we begin a new calendar year, I have decided to explore specific parts of history that I find intriguing, yet not often discussed. My first post is about the first Red Scare.

Well, more specifically, about Emma Goldman.

Goldman was a radical activist who fought for women's and workers' rights during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly during the second Industrial Revolution. Her advocacy occurred alongside the fear of Communist uprisings, which led to the Palmer Raids executed during the First Red Scare.

First, if you are new to my Substack, my name is Aryn. I’m a genealogist and researcher working to help others learn more about their family history, the social history of the world those ancestors lived in, and how to learn all about it to shape well-rounded factual accounts about the people who came before us. To learn more about this substack and my love of history, family history, and genealogy, head here!!

In the aftermath of World War I, as fear and paranoia gripped America, one of the most influential voices for workers' rights and women's liberation found herself caught in the crosshairs of government repression. Emma Goldman, the fierce anarchist philosopher and activist known as "Red Emma," became a primary target of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer's infamous raids against suspected radicals.

But really, if I start there, I’m jumping again. To better understand Emma Goldman, you must understand The Haymarket Affair and her failed1 marriage to Jacob A. Kersner.

The Haymarket Affair - 4 May 1886 - Chicago, Illinois

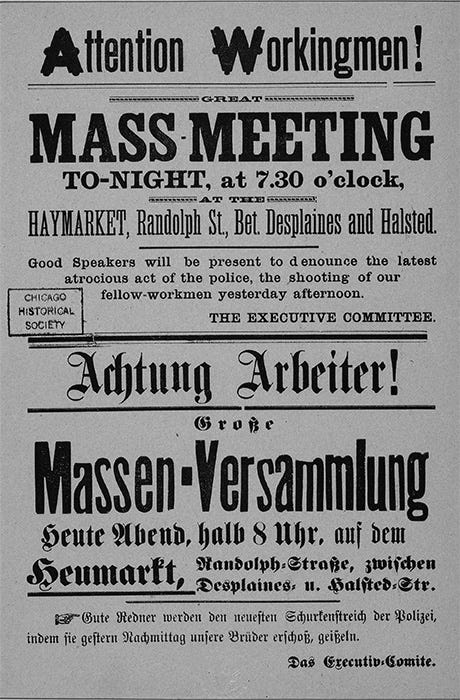

On Tuesday, 4 May 1886, a group of peaceful labor workers convened in the Haymarket in Chicago to protest the police brutality that had taken place the day before in front of the McCormick Reaper Works Factory.

The protest was designed to once again point out the need for better work policies. What were the workers asking for? Something we take for granted these days: an 8-hour workday.

As early as 1835, workers and laborers (and their unions) were petitioning for shorter workdays. Before the 8-hour workday, trade and labor workers could work up to 100 hours a week and take home as little as $10—around $380 in 2025. By 1886, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Union set a 1 May deadline for achieving the 8-hour workday goal by any means necessary.

When 1 May came and went, widespread protests and strikes took place across the United States. This upheaval and striking set the stage for the Haymarket Affair.

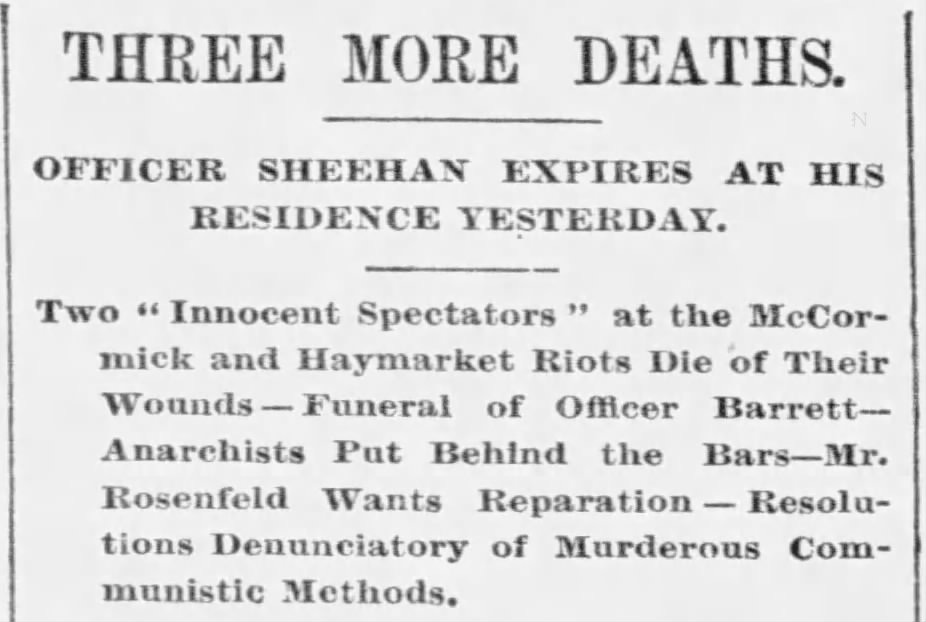

The day before the Haymarket Affair, a clash between the non-strikers and strikers escalated at the McCormick Reaper Works Factory. Like in modern times, workers on strike formed a line and shouted at the scabs (strikebreakers) as they crossed the line. The strike grew heated, and strikers began to fight with the scabs – two police officers on the scene fired into the crowd, killing at least two workers and wounding others.

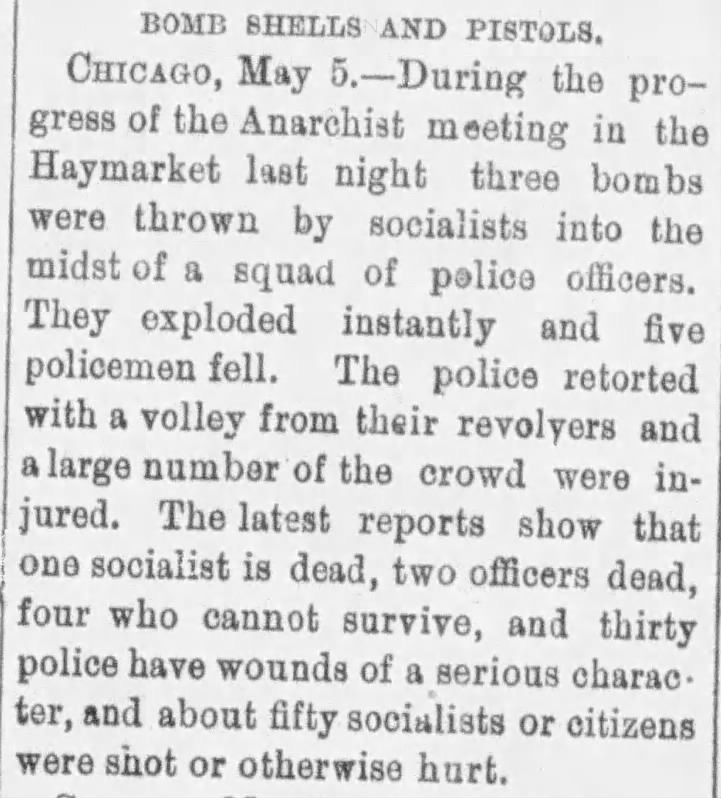

On 4 May 1886, at the Haymarket, strikers gathered once more and, once more, were met with violence. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb into the crowd. Upon the explosion, surrounding police fired into the crowd. Seven police officers and at least four civilians were killed, and dozens were injured.

After arriving in the United States in 1885, Emma worked in garment factories. She was very aware of the long, grueling hours expected of the employees and the need for reform for better hours and better pay. Emma Goldman followed both the 8-hour workday strikes and the explosive events in the Haymarket.

Inside the factory that she worked, Emma Goldman met her husband, Jacob A. Kersner, which leads me to the second event in her life that defined the legacy she left behind.

Like any other woman of her time, Emma was expected to marry, and she did. In February 1887 she and Jacob Kersner, a fellow Russian immigrant, married. The marriage was a bust from the start, and Emma quickly learned that the freedom she craved and the life she thought she could live as a married woman would never be. After months of trying, Emma divorced Jacob and moved to Connecticut.

A few months later, she returned to New York, remarrying Kersner after he threatened suicide if she did not, but the marriage was doomed from the start.

While Emma’s personal life was in upheaval, eight anarchists were arrested for the bombing in the Haymarket, even though there was little proof of their involvement. Four of the accused were hanged. The other four were later exonerated.

By 1888, Emma petitioned for a divorce a second time rather than rekindling the marriage like her family wanted. Her decision to end the union led her family and her faith to shun her.

Between the Haymarket Affair and her family turmoil, Emma left the Jewish faith she was raised in and embracing the fight of the anarchists.

The Second Industrial Revolution

When we are taught about the Second Industrial Revolution, we tend to focus on all the wonders and amazing inventions that were developed during that time, but those inventions were born in brutal working conditions for the working class. When Emma Goldman arrived in America as a teenage immigrant, she witnessed these conditions firsthand. She found herself surrounded by women and children laboring in dangerous factories for pennies, denied basic rights and dignities, which ignited the flame of resistance in her.

Emma Goldberg was convinced that the only true liberation required completely reimagining society's power structures.

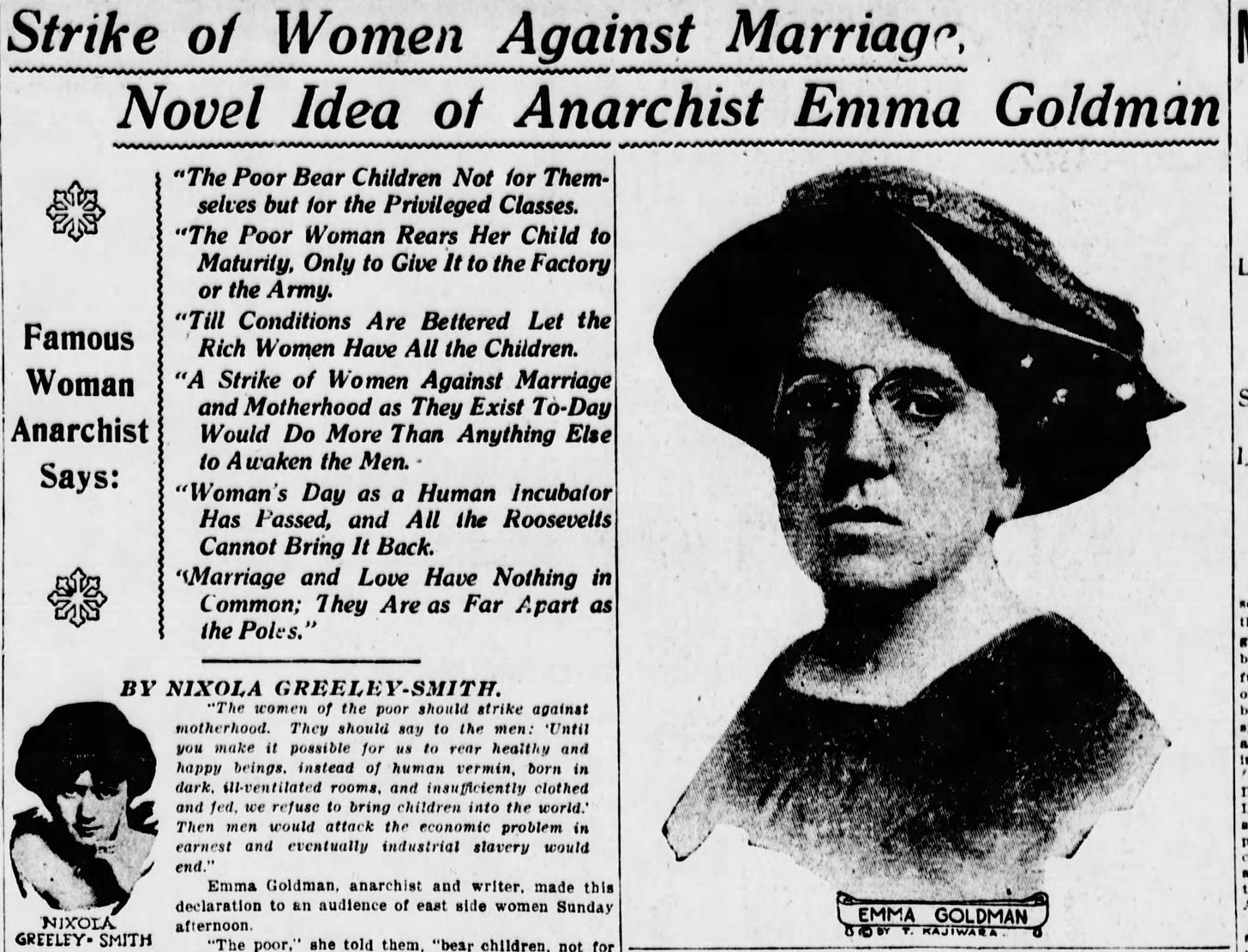

Goldman's advocacy was revolutionary for her time. While the suffragette movement had been going strong for thirty-seven years, many suffragists focused solely on gaining the vote. Emma argued that women's emancipation required economic independence, access to birth control, and freedom from traditional marriage expectations. "Marriage and love have nothing in common," she declared loudly, challenging Victorian sensibilities on the cover of newspapers and her speaking tours.

In a time when it was considered scandalous and unladylike, Emma Goldman spoke openly about sexuality and reproductive rights.

For working women, Goldman was a fierce champion. She organized female garment workers, supported strikes, and demanded equal pay and safer conditions. Her "Mother Earth" newspaper regularly published exposés of workplace abuses and calls for labor solidarity. She saw women's and workers' rights as inherently interconnected struggles against patriarchal capitalism.

For the next thirty years, Emma Goldman, along with other known anarchists like her lover Alexander Berkman, used her time and her voice to bring awareness to the unbalance between women and men in the United States. She published newspapers and books, spoke around the country, and worked alongside others seeking freedoms only obtainable from the emancipation of women's working-class role.

Then, two more things happened… First, the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. In 1917, Vladimir Lenin and his Red Army liberated Russia from the crown. The communist party descended on the Winter Palace, killing the Tsar and his family. An uprising inspired and fueled by the poor handling of World War I by Tsar Nicholas II.

Second, WWI’s effect on the economic landscape in the United States and the following Influenza Pandemic (aka The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918).

Americans were angry with the United State’s involvement during World War I from the moment conscription was put into play.2 Then, at the end of the war, the Influenza Pandemic swept across the country, only adding to the growing depression due to a lack of jobs brought on by the end of the war, the lack of need for war production, and the returning soldiers who needed jobs to return to.

While America struggled to move forward, word of the Bolsheviks overthrowing their government carried around the globe. Could that happen here?

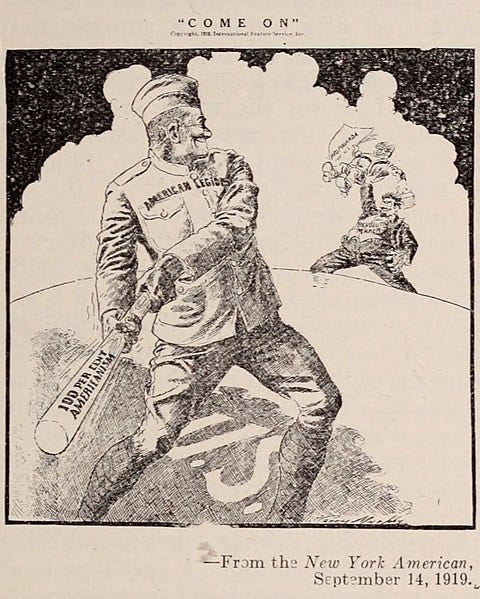

In the post-World War I landscape, America was finally seen as a World Power, and this new World Power was growing increasingly scared that what happened in Russia could happen here.

This is why Goldman's radical vision made her dangerous in the eyes of authorities.

Enter A. (Alexander) Mitchell Palmer - the Attorney General of the United States of America.

As paranoia grew, so did the government's need to squash it. When the Palmer Raids began in 1919, targeting suspected anarchists and communists, Emma Goldman was easy to single out. Her name had been splashed across newspapers for years, and she was never subtle with her words; plus, she was already in prison.

First arrested in 1915 and again in 1916 for "lecturing and distributing material in support of birth control." Emma was imprisoned in 1916 for the second round of this offense. Then again, in 1917, she was arrested a third time, this time for speaking against the draft laws. Sentenced to two years in Minnesota prison, that is where she sat when Palmer began his raids.

The raids, conducted without warrants and marked by brutal violence, represented one of the most severe attacks on civil liberties in American history. Thousands were detained, and hundreds of foreign-born radicals, including Goldman, were deported.

On December 21, 1919, Goldman and 248 other radicals were forcibly placed aboard the USS Buford, nicknamed the "Soviet Ark," and deported to Russia. The woman who had spent three decades fighting for American workers' rights and women's liberation was expelled from the country she had called home since adolescence.

The silencing of Goldman represented more than just the removal of one activist. It marked an attempt to suppress the broader movements for social justice she embodied. Her persecution served as a warning to other activist, and deterring them from speaking out about controversial issues. Yet, in the end, her ideas proved impossible to deport. Her writings on feminism, workers' rights, support of the LGBTQ community and social liberation influenced generations of activists to come.

Today, as debates rage over immigration, workers' rights, and women's autonomy, Goldman's story remains remarkably relevant. The Palmer Raids remind us how quickly civil liberties can be sacrificed to fear and nationalism. Meanwhile, Goldman's insistence that true liberation must address both economic and social oppression continues to resonate.

Her famous declaration – "If I can't dance, I don't want to be part of your revolution," – captures the spirit of a woman who fought not just for fundamental rights but for the full flowering of human potential. Emma Goldman's revolutionary voice still speaks to us across the century in an era of continued struggle for workers' rights and women's equality.

How To Research Revolutionaries in Your Family Tree

While Emma Goldman was a prolific writer and activist, making her easy to search, maybe your ancestor was equally part of the Suffragette and Labor Movements but not a public speaker like Goldman. Still, there are ways to research your ancestors who chose to fight for women's liberation and labor laws.

Newspapers are still a wonderful place to begin. You never know what you will find written in an old newspaper or what image you may see. If you are researching a relative who worked in a factory in Chicago in 1886, there is a good chance they were involved or at least affected by the Labor strikes.

Union Memberships are another place to look. Sites like the Society of American Archivists and the Library of Congress have extensive collections containing information about the active unions during the Haymarket Affair. Plus, you can contact specific Unions directly to see if they have their own archives.

Census Records and Directories both list occupations. If you cannot locate one, look for the other, but either will give you a location where your ancestors lived during the time of the strikes and also let you know their occupation. Census records available through the National Archives and Directories through the Library of Congress, but can also be accessed via local libraries in the location where your ancestors lived.

Court and Police Records are important because if your ancestor was arrested, there would most likely be documentation of that transaction. Search local county archives, police department records, or state repositories for court transcripts or jail logs. You can also try FamilySearch’s United States Court Records online.

Deportation Records are another must if your ancestor suffered a fate similar to Emma Goldman's. Alien Files (or A-Files) can be found in the National Archives (and other places, too).

These are only a few places to look for more information about an ancestor who may have taken part in the labor strikes in the late 1800s and early 1900s: passenger lists, Oral Histories at local historical and genealogical societies, employment records, and even church records (because sometimes our ancestors were prayed for and it was recorded in a church bulletin).

Never forget to think outside the box when researching your ancestors!! Some of the best information may be hidden in places we decided not to look. So, exhaust your resources and return next week when I discuss Jean Seberg. She was made famous from her role in the film Breathless [à bout de souffle], a Jean-Luc Godard film, and infamous by J. Edger Hoover, FBI surveillance under COINTELRPO, and her support of the Black Panther Party.

To learn more about about Genealogy by Aryn - head over to GenealogybyAryn.com, stop by and say hello on Bluesky - TikTok - Instagram - Facebook - YouTube.

Be sure to check out my Etsy Shop and stop by my Genealogy Shop.

By “failed,” I’m referring to her family's opinion and the community Emma lived in upstate New York.

Conscription is why we have access to World War I draft cards and it was part of the Selective Service Act of World War I, requiring men between the ages of 21 to 45 to register for military service.

I made a short comic about my family history that is somewhat related to this story.

https://drucomics.substack.com/p/bad-things-happen-you-can-still-live

Thanks. I found that really interesting.