On May 1, 1886, nearly thirty-five thousand American workers in Chicago walked off their jobs with a simple demand: an eight-hour workday. At the time, they were working upwards of 10 to 14 hours a day, six days a week, and they wanted change and to be treated fairly. It sounds like a reasonable request for basic human dignity, right? But that day would end in tragedy and forever change how America viewed labor movements and immigrant workers. People remember that day as The Haymarket Affair.

Eight hours for work, eight hours for sleep, eight hours for what we will!

The slogan, “Eight hours for work, eight hours for sleep, eight hours for what we will!” became the rallying cry that echoed through America’s industrial cities as workers fought for something we take for granted today – only eight hours of work. Back in 1886, most industrial workers labored 10 to 14 hours per day, six days a week – and sometimes, even seven. They worked in dangerous conditions for wages that barely supported their families. If they decided to take a day off or even felt sick, there was no such thing as paid holidays, sick leave, or workers' compensation.

The movement wasn’t born from radical politics. It came from exhausted workers who simply wanted time to live and not to watch all their hard-earned money slip away in company-owned housing, grocery stores, and more. They wanted time to see their children awake or to read a book and walk in the sunshine.

Laborers being able to work an eight-hour day represented more than reform. It was about reclaiming human dignity in an age of industrial giants and a class divide so wide it was difficult to see across the chasm.

Chicago became the epicenter of the eight-hour movement, with its massive industrial workforce and strong immigrant communities. The city’s factories employed thousands of German, Polish, and Bohemian immigrants who brought with them traditions of worker solidarity from their homelands.

On May 1, 1886, over 40,000 workers in Chicago participated in a general strike. The atmosphere was festive and hopeful. Families joined the marches, children carried banners, and workers walked through the streets, singing as they went by.

For one shining moment, it seemed like the eight-hour dream might become a reality. Regardless, the hope and camaraderie lasted exactly three whole days.

On May 3, violence erupted at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company when police opened fire on striking workers, killing several. Outraged labor leaders called for a protest meeting the following evening at Haymarket Square.

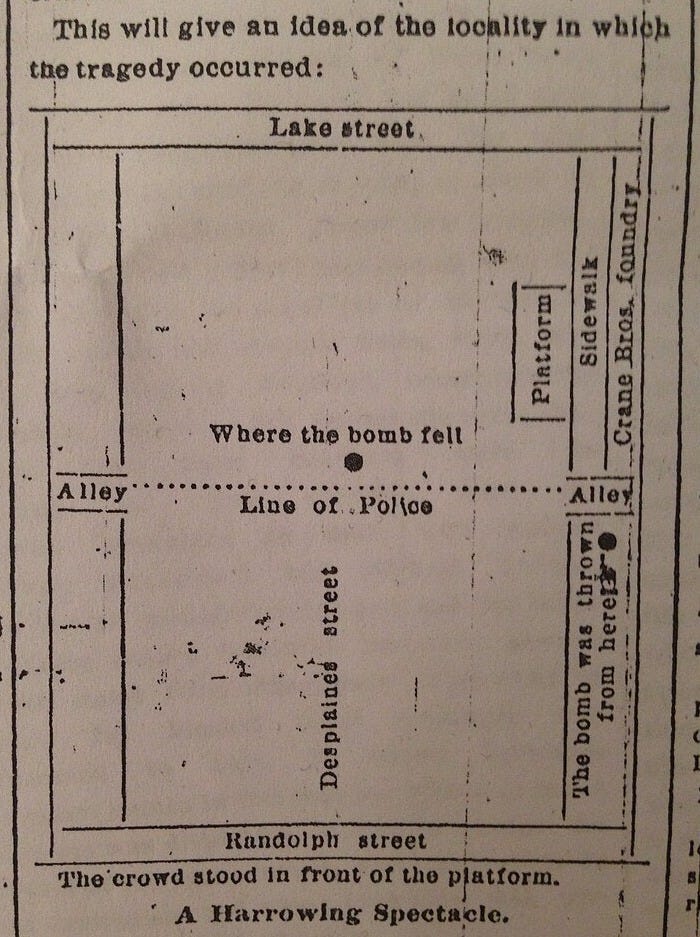

May 4, 1886, started peacefully. About 3,000 people gathered in Haymarket Square, a space in Chicago known for its fruit and vegetable stands, livestock, and hay. It was also known as a gathering place and a public square often used for public meetings, speeches, or political events. These are the things that made the Haymarket the perfect location to hear speeches about workers' rights and have the strikers gather to air their grievances.

That day, still in late spring, the temperatures were cooler, and rain began to fall, thinning out the crowd. Samuel Fielden – one of the men wrongly accused, arrested, and tried for the bombing – had stepped down from the speaker’s wagon as the police advanced in an attempt to disperse the remaining protesters.

In that instant, everything changed: Someone threw a bomb of dynamite into the police ranks.

The chaos was immediate.

One policeman died instantly, while six others were mortally wounded.

The police opened fire on the strikers in retaliation.

Then, the remaining protestors opened fire on the police.

As the situation escalated, and both sides volleyed bullets at each other, more people were wounded, and more died.

When the smoke cleared, four civilians were dead, as were seven police officers, and dozens more lay wounded on the ground in the Haymarket.

It turned out, the bombing provided a perfect excuse for the police to take action, and ruthlessly crackdown on the labor movement. Within hours, police began rounding up known anarchists – a group of people who were fighting for labor reform by abolishing hierarchical power and the capitalist state – and other known labor leaders. History would show that none of these people had anything to do with the bombing.

Yet, the press whipped up anti-immigrant hysteria, painting all foreign-born workers as dangerous radicals.

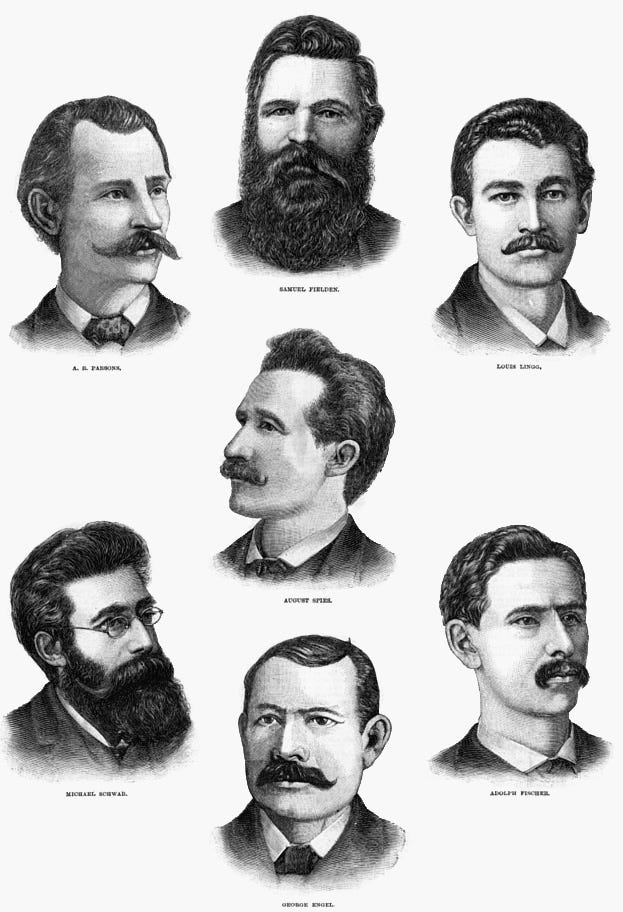

August Spies, Samuel Fielden, Adolph Fischer, Albert Parsons, Michael Schwab, George Engel, Louis Lingg, and Oscar Neebe were charged with murder. Still, none of them were charged with throwing the bomb. The actual bomber was never identified. So, the local officials had the arrests made for allegedly inspiring the violence through their speeches and writings.

Of the eight arrested – Albert Parsons, Michael Schwab, George Engel, Louis Ling, and Oscar Neebe, were not even at the Haymarket when the bomb went off.

The trial was a sham by any modern legal standard. Judge Joseph E. Gary was openly biased, going so far as to allow Henry L. Ryce to handpick jurors. Ryce made a point of excluding anyone who might sympathize with the defendants. Gary was also well known for being anti-immigrant and anti-union. He ruled in favor of the prosecution, even when the evidence was largely circumstantial, and in the end, he refused to grant a retrial – after it became apparent that the whole trial was deeply flawed.

On November 11, 1887, August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel. Louis Lingg died in his cell, reportedly by suicide. The remaining three, Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, and Oscar Neebe, had their sentences commuted to life in prison. Six years later, Fielden, Schwab, and Neebe were pardoned by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, who declared the trial unfair.

For immigrant families and laborers in Chicago,

the Haymarket bombing was a devastating lesson in the one-sided American justice system. Immigrants who were among the most active in the eight-hour movement suddenly found themselves viewed with suspicion and hostility. Families who had marched proudly on May 1 now aired their grievances behind closed doors, afraid that their participation in the movement would mark them as dangerous radicals.

Or worse, they would end up like the wrongly accused men who paid with their lives.

It felt like an insult to injury, especially since so many immigrant workers had come to America fleeing political persecution, only to find themselves caught in a new web of suspicion and fear in their new home. The Haymarket Affair taught them that in America, fighting for workers' rights could be just as dangerous as challenging the old country's kings and emperors.

The Haymarket Affair effectively ended the eight-hour movement in America for a whole generation. Labor organizers faced branding as foreign agitators and anarchists. This is the same period when the first Red Scare took place, and the Pullman Raids swept the country.

In the end, the eight-hour day wouldn’t become standard until the 1930s, nearly fifty years later.

But internationally, the Haymarket Martyrs became symbols of the worldwide struggle for workers’ rights. May 1 became International Workers’ Day, celebrated everywhere except in the United States, where Labor Day is observed in September—a deliberate attempt to distance American labor from the Haymarket legacy.

Behind the headlines and historical significance were real families whose lives were forever changed. Wives became widows, children grew up without fathers, and entire communities lived under the shadow of suspicion. The promise of America, also known as the "American Dream," that hard work would be rewarded with opportunity, felt hollow to many immigrant families after the Haymarket incident.

Don’t forget to give this post a heart and a restack!

RESOURCES:

Here are some places to research your ancestors who were, or may have been, connected to the Haymarket Affair.

Chicago Anarchists on Trial: Evidence from the Haymarket Affair, 1886-1887: held by the Chicago Historical Society and available through the Library of Congress, offers over 3,800 images of original manuscripts, broadsides, photographs, prints, and artifacts. This collection documents the events, the people involved, and the legal proceedings, providing a valuable resource for genealogical research.

Illinois Genealogy Trails: this site provides a dedicated page on the Haymarket Riots, including lists of police officers killed, details of the event, and related historical context. While it primarily focuses on the event, it may help identify individuals who were present or involved, especially law enforcement personnel and labor activists.

Chicago History Museum: has collections and archives related to the Haymarket Affair, including personal papers and records that may be useful for tracing family connections.

The Haymarket martyrs are commemorated at Waldheim Cemetery, now Forest Home Cemetery, in Forest Park, Illinois. Cemetery records and monument inscriptions can be useful for tracing descendants or relatives of those directly involved

And as aways, remember to check local libraries, local newspapers, and local genealogical societies.

To learn more about Genealogy by Aryn - head over to GenealogybyAryn.com, stop by and say hello on Bluesky - Instagram - Facebook - YouTube

Be sure to check out my Etsy Shop and stop by my Genealogy Shop.

Looking to learn more about writing your family history? Check out From Research to Novel!

For more information about my Genealogical Services visit GenealogyByAryn.com or email me at aryn.genealogy@gmail.com. For more information on Writing Services - visit ASYounglesAuthor.com

You made it to the end!! I’d love to hear your thoughts!! If you have a few minutes, consider taking my survey. Your input helps me make improvements to this substack! Thank you!

Just the history lesson Americans need to hear today.

That was really interesting. It prompted me to check out the history of the 8 hour day in NZ. Our Labour Day is celebrated on the 4th Monday of October every year. The move towards the 8 hour day began in 1840. The history of the 8 hour day in NZ is a very different one to yours ... https://nzhistory.govt.nz/page/labour-day-0#:~:text=New%20Zealand%20workers%20were%20among,parades%20in%20the%20main%20centres.