Los Angeles is a city deeply rooted in Mexican heritage, a history often overshadowed by Hollywood’s glitz and glamour. The 1931 La Placita Raid, a pivotal event in the city's past, exemplifies this tension. This article explores the raid's historical context, its devastating impact on the Mexican-American community, and its lasting lessons for contemporary society.

Setting the Scene: Olvera Street and La Placita Park

First, let me tell you a little about where La Placita Park, also known as the Los Angeles Plaza, is located and where the La Placita Raid took place.

Situated between Main St. and North Alameda, Olvera Street butts up to a third street, W. Cesar Estrada Chavez Avenue. It sits across from Union Station, on the eastern side of North Alameda. Once you climb a short hill to the Paseo de la Plaza, the mouth of Olvera Street sits on the right-hand side, just past La Plaza United Methodist Church, and directly before Chiguacle Sabor Ancestral de Mexico, Mexican Restaurant.

A Community at the Heart of Los Angeles

The surrounding historical area is known as the El Pueblo de Los Angeles district of Los Angeles. It gets its name from the origins of Los Angeles.

The full name of Los Angeles - El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río Porciúncula - reflects the city's origins, rooted in a time before 4 April 1850, when Los Angeles was still part of Mexico.

Mexico’s influence is felt throughout this city. From street names like La Cienega (the swamp) or La Brea (the tar - and yes, the La Brea Tar Pits is actually “the Tar, Tar Pits). To locations like Hermosa Beach (Beautiful Beach), or Playa del Rey (Beach of the King). The lasting influence of our Mexican heritage is evident in street names, food, culture, music, and on and on, shaping the city in countless ways we take for granted on a daily basis.

When you’re in Los Angeles, you can feel the history and essence of its Mexican heritage all around. It’s electric. The problem is, most people come here searching for Hollywood, not Los Angeles. Hollywood is a whole other ball of wax—not a bad one, just different—but I’ll save that for another post.

Olvera Street is a snapshot of Los Angeles’s great history. The street, or calle, is composed of red bricks and tree lined with Moreton bay fig trees that boast large, thick, deep green leaves and buttress roots that stretch outward from the trunk, fanning into the earth as if several trees had gathered at a single heart. Down the center of the brick path are small shops set up inside wooden carts, and flanking either side are places like the Avila Adobe, the oldest house in Los Angeles, as well as shops selling trinkets and souvenirs, handmade Mexican dinnerware, authentic Mexican clothing, and statues of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Oh, and food. Lots of amazing and delicious Mexican food.

On the northern end of Olvera Street is the Italian Hall. A holdover from when Olvera Street was Little Italy. A short lived location in the annals of Los Angeles’ history. Las Anitas Mexican Restaurant has been serving locals and tourists from inside the hall since 1947. If you look around, you’ll find a plaque noting the building’s Italian heritage.

At the southern end of Olvera Street is the El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument, which is surrounded by museums, like The Pico House. A building once owned by Pio Pico, the last governor of California when it was still part of Mexico.

El Pueblo de Los Ángeles is also home to La Placita Park, where our story will begin.

The Day Everything Changed: The La Placita Raid

It was a quiet afternoon in February 1931, and families were gathering at La Placita Park. The weather was cooler, high fifties or low sixties, but the California sun was warm, as were the familiar comforts of their community. That is what Olvera Street is and was — a community. It was a Thursday. An ordinary, run-of-the-mill day, but that would change very quickly.

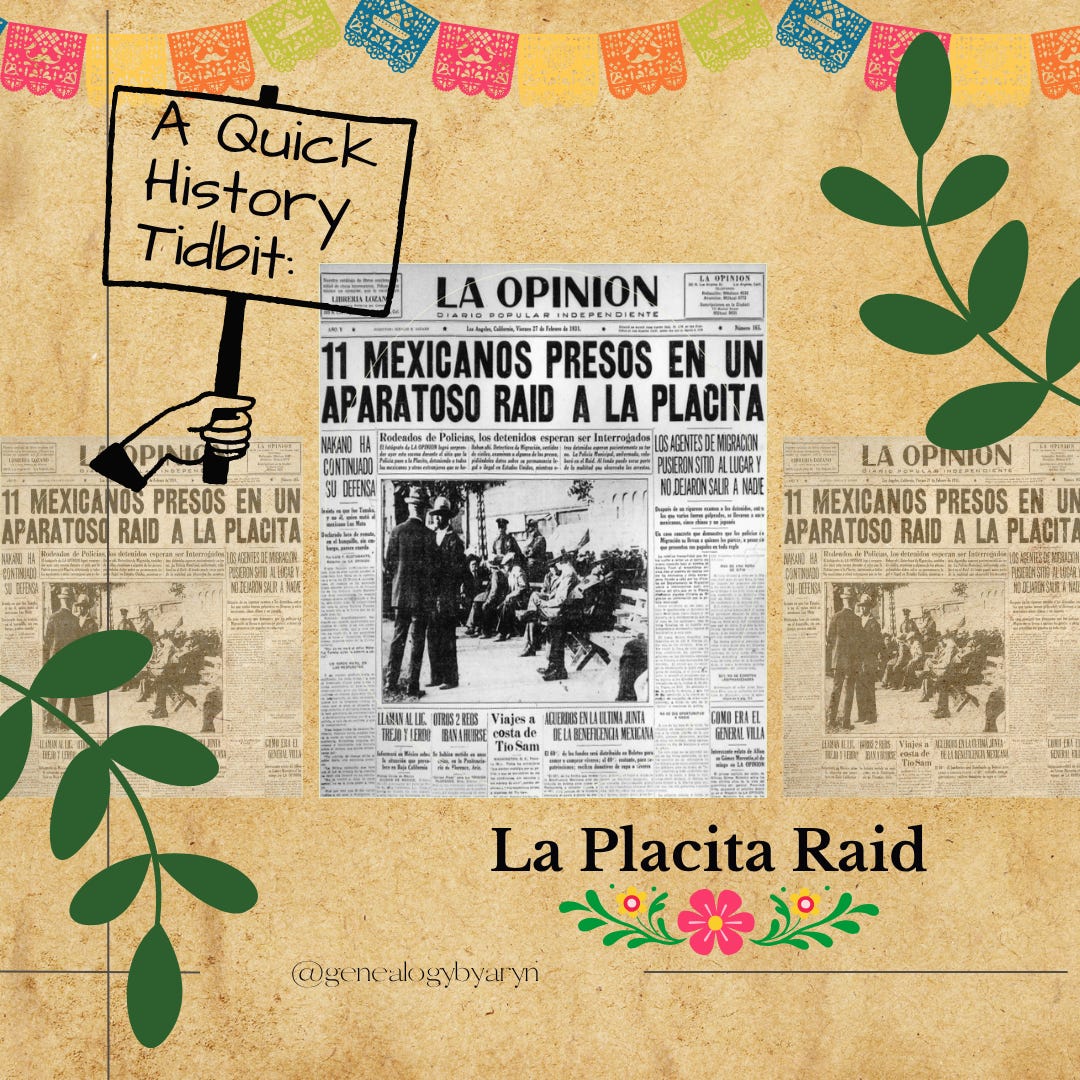

That day, Thursday, 26 February 1931, was the beginning of one of the most notorious immigration raids in American history. It marks the beginning of a systematic campaign that would tear apart Mexican-American families across the country, and while it didn’t start next to Olvera Street, the La Placita Raid would be used as a model across the US. It was a calling card, if you will, to set the standards of what the federal government was willing to do to reach its anti-Mexican objective.

La Placita Park is a small public space that served as a vital community gathering place, where families socialized, children played, and the sounds of Spanish mingled with English in the familiar rhythm of immigrant life. Mariachi music wafted on the same breezes that carried the cinnamon of churros, the bright crispness of fresh cilantro, and savory scents of onions and peppers sautéing.

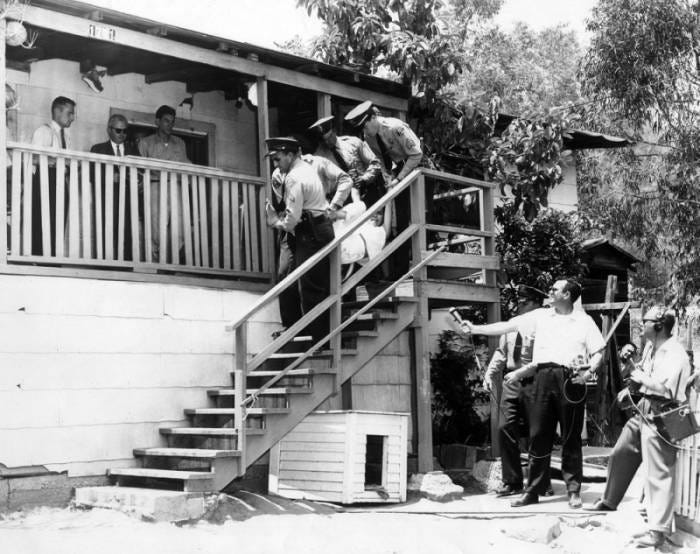

On that ordinary Thursday, the peaceful atmosphere of La Placita Park was suddenly shattered. Armed immigration officers - some in military uniforms - sealed off the plaza’s perimeter. Plainclothes officers, who had been mingling with the crowd, revealed themselves, brandishing guns and batons. They blocked every exit, ensuring no one could escape, while flatbed trucks circled the park, transforming the scene into something that resembled a military operation.

The Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS), along with assistance from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) demanded that everyone in the park immediately present their immigration documents. Anyone unable to provide proper identification would be arrested on the spot.

Around four hundred people were in the park when the immigration officers ambushed them, and at least a dozen were immediately deported after being taken into custody. Many others were arrested that Thursday in February 1931, but most were released.

A City in Fear: The Aftermath and Ripple Effects

The message was delivered and it rippled through Los Angeles: the La Placita Raid made it clear to the Mexican American community that they were vulnerable and powerless against the Immigration Department, which had demonstrated that even long-time residents could be targeted for deportation.

National Impact: The Raid as a Model

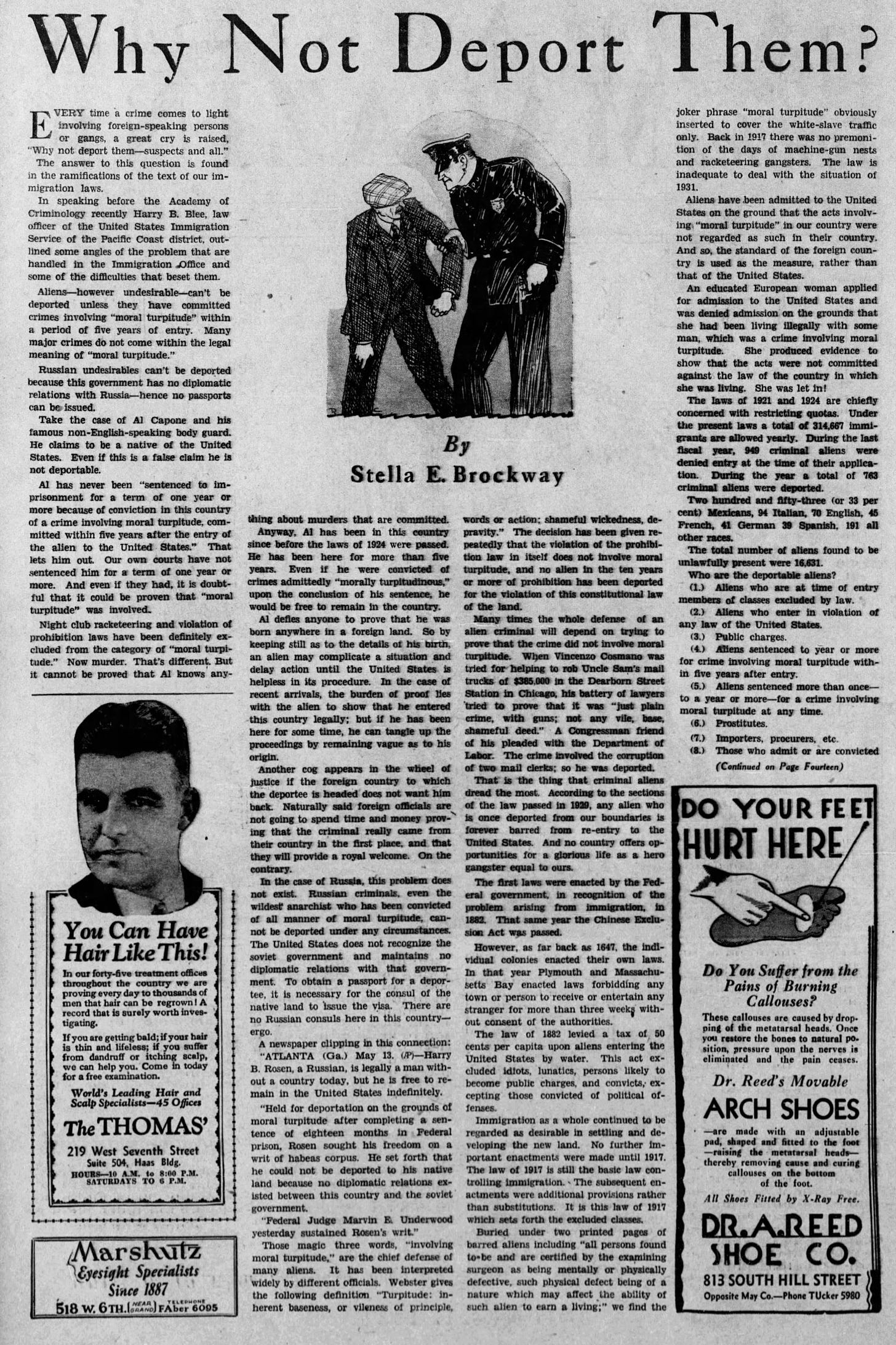

The La Placita Raid didn't occur in isolation. By 1931, the Great Depression had plunged the United States into economic despair. Unemployment soared, businesses collapsed, and frightened Americans looked for someone to blame for their suffering.

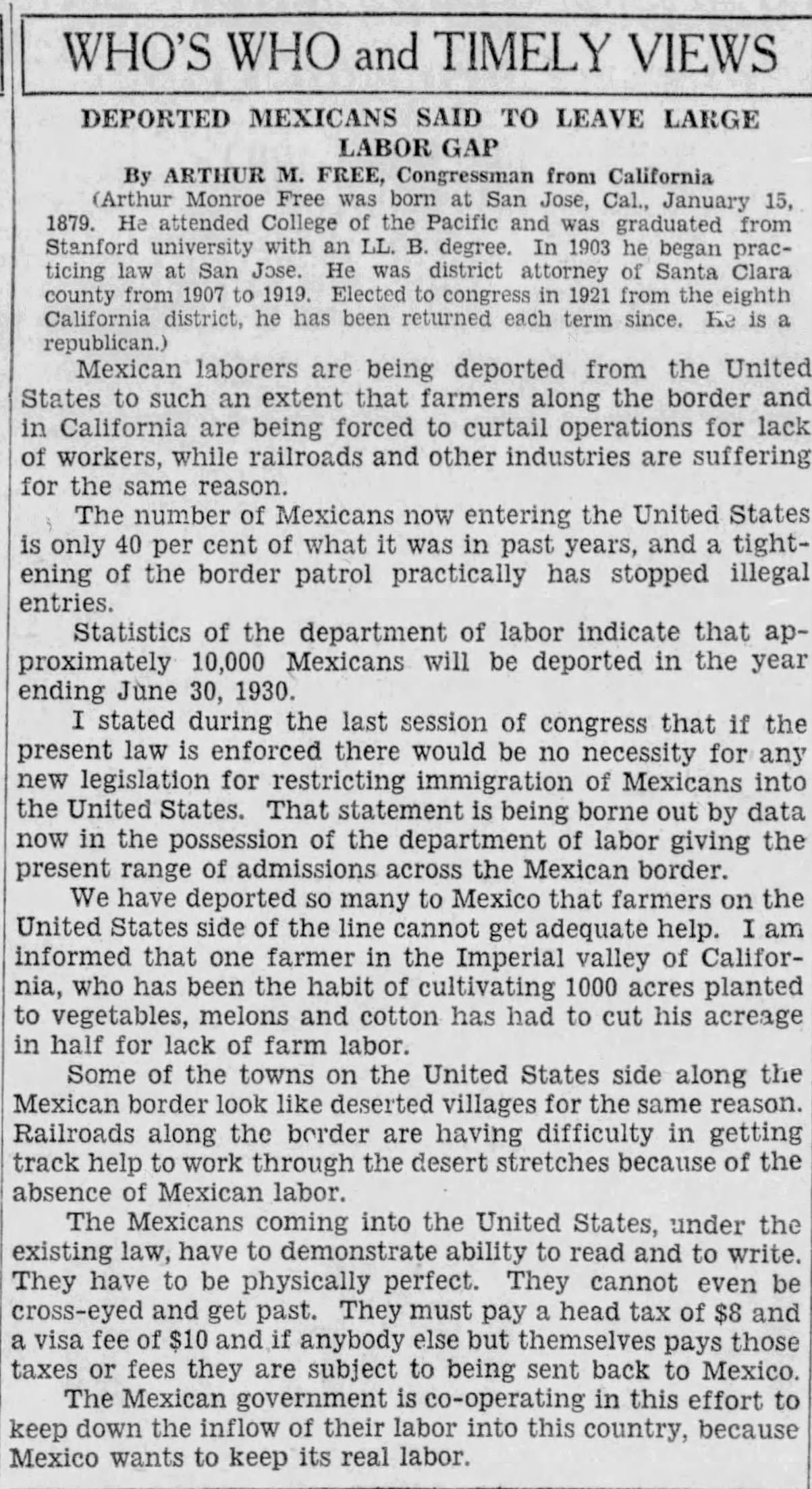

Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans became convenient scapegoats accused of stealing jobs from "real" Americans.

The economic anxiety of the growing Great Depression fueled the escalating anti-Mexican sentiment sweeping across the country. Politicians and local officials, eager to appear tough on what they portrayed as an immigration problem, began calling for mass deportations.

The La Placita Raid represented the first prominent public display of this new aggressive approach to immigration enforcement.

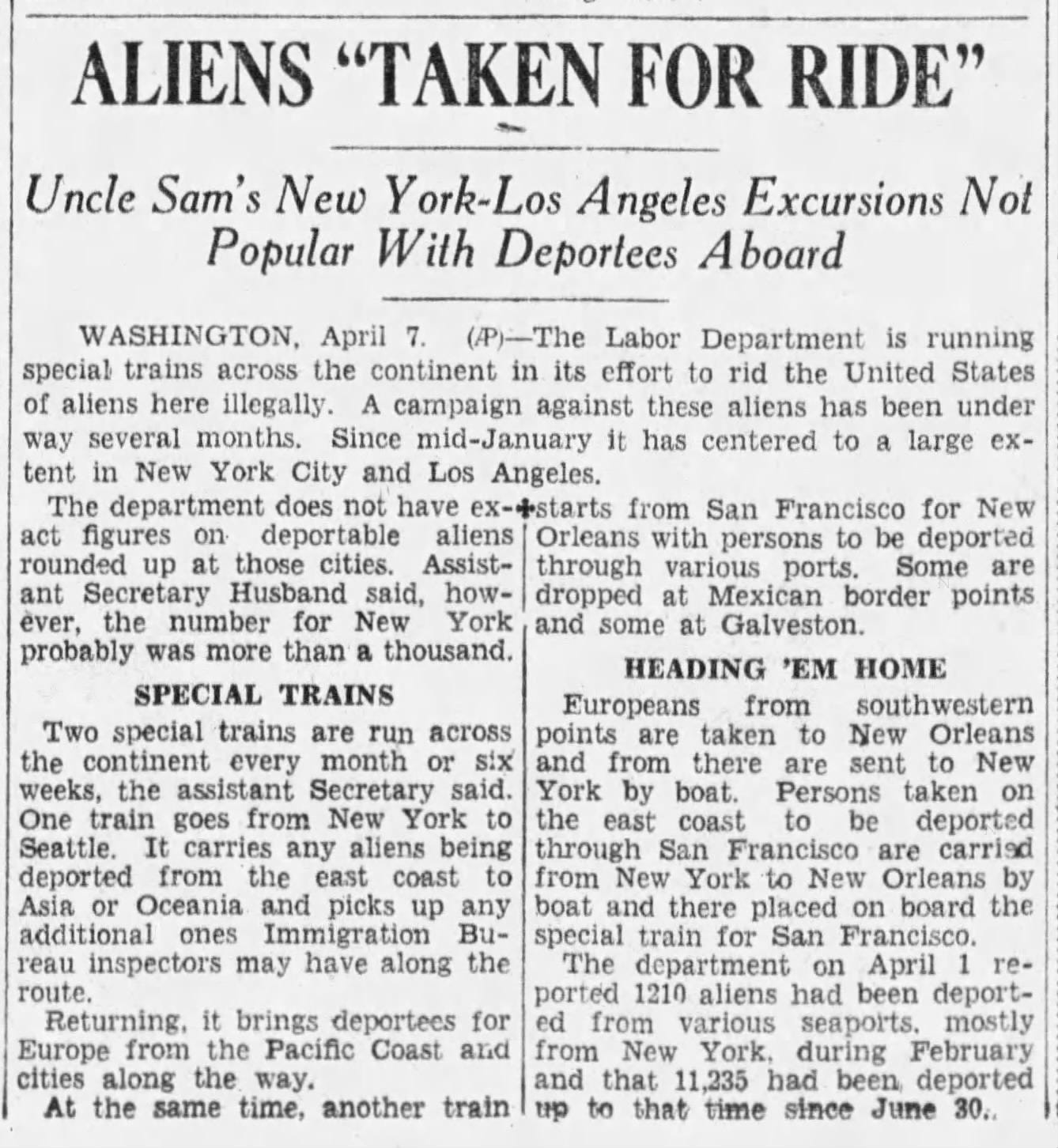

With its overly dramatic public arrests and mass deportations, the La Placita Raid was splashed on the pages of newspapers from coast to coast. Even more troubling, the raid’s high profile and apparent “success” prompted authorities across the country to launch similar operations.

In the end, the raid became a model for aggressive immigration enforcement, helping to normalize the use of public raids and mass deportations throughout the 1930s. These campaigns would ultimately affect the lives of hundreds of thousands, and upwards of 1.8 million, people of Mexican descent.

The Human Cost: Families and Communities Torn Apart

The impact of the La Placita Raid extended far beyond the people arrested that day. The raid sent shockwaves through Mexican-American communities across Los Angeles and beyond. Families lived in constant fear that they could be next. Many chose to leave voluntarily rather than risk the trauma of forced removal.

What made the situation particularly tragic was that many of those targeted were American citizens. Children born in the United States found themselves deported to a country they had never known. Families were separated, with some members holding citizenship while others did not.

The raids made no distinction between recent immigrants and families who had lived in the United States for generations.

The psychological impact was profound and lasting, especially on the children who witnessed the raid or lived through its aftermath. It was another example of communities that had taken generations to build being scattered and destroyed. Something the Mexican American community would experience again, less than thirty years later, when they were forcibly removed from Chavez Ravine to make way for Dodger Stadium.

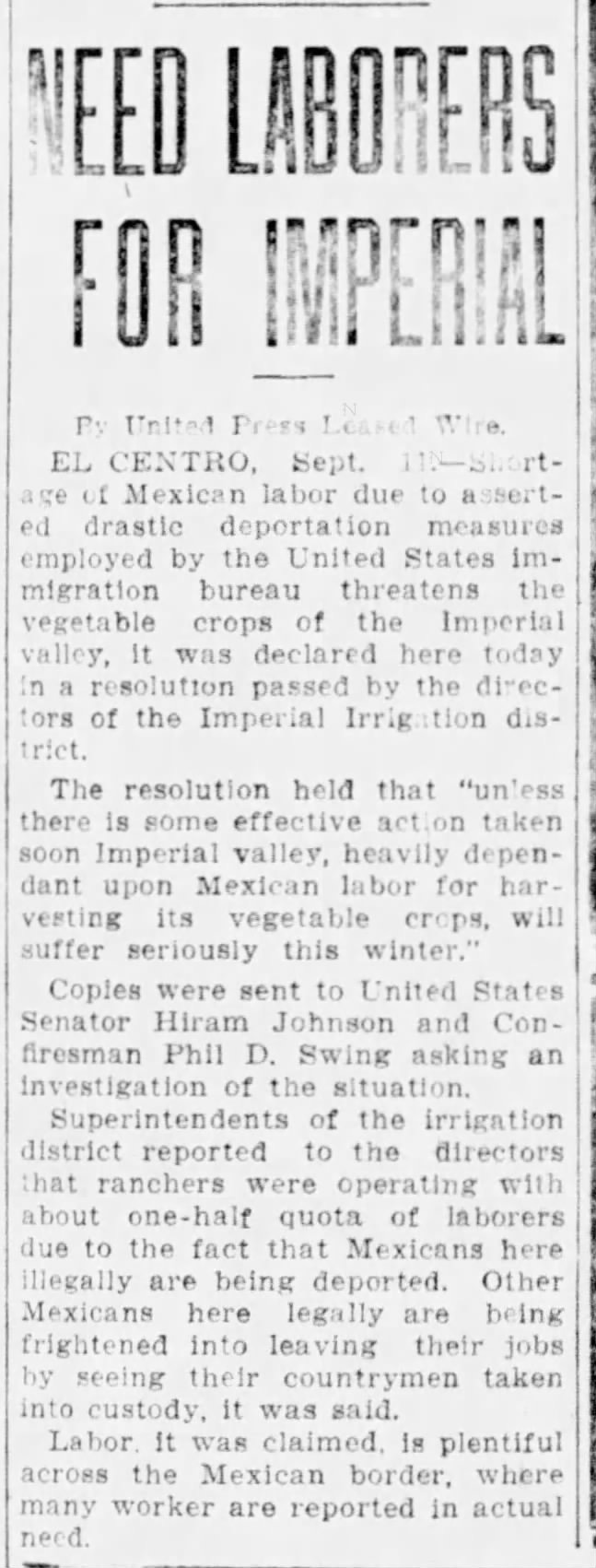

Additionally, the economic contributions of these families - their businesses, labor, and tax payments - were all lost to them and to the communities they left behind.

The Broader Campaign: Mexican Repatriation

The La Placita Raid of 1931 was a highly publicized event that brought national attention to the Mexican Repatriation, a campaign that had begun in the late 1920s and continued throughout the 1930s. During this period, hundreds of thousands—and possibly up to 1.8 million—people of Mexican descent, including many U.S. citizens, were forcibly removed, pressured to leave, or deported from the United States. The year 1931 marked the peak of these removals, with the La Placita Raid serving as a symbol of the broader and ongoing efforts against the Mexican and Mexican American communities.

The term "repatriation" was deliberately chosen to make the program sound voluntary and humane, but the reality was far different. While some individuals decided to leave on their own, others were coerced, threatened, or simply swept up in raids, like the one at La Placita. The majority of those affected were American citizens.

Deportation campaigns took place at all levels of government, from federal immigration authorities to local police departments. Cities organized special trains to transport deportees to Mexico, often with great fanfare and publicity designed to intimidate others into leaving voluntarily.

After the raid, immigration enforcement became increasingly militarized, with raids conducted in neighborhoods, workplaces, and public spaces.

The conditions of fear it created persisted long after the Depression ended.

Yet, despite the promises from the President and the Federal Government that the mass deportations would solve the economic problems plaguing the US, they did not. Research has shown that the removal of Mexican workers caused more harm to local economies than anything else. They reduced employment opportunities for remaining workers and disrupted established labor markets. The very communities that had demanded deportations often found themselves worse off economically.

Lessons Learned: Civil Rights and the Dangers of Scapegoating

The La Placita Raid serves as a stark reminder of how economic anxiety can fuel scapegoating and erode civil liberties, underscoring the need for vigilance in protecting the rights of all communities during times of crisis. It demonstrates the dangers of allowing fear and prejudice to guide immigration policy and the long-lasting damage that can result from mass deportation campaigns.

Another takeaway from the raids is the importance of due process and civil rights protection. The people who were arrested that day had no opportunity to prove their legal status or citizenship.

The people were ambushed and arrested on the presumption of guilt based on appearance or accent, both of which violated fundamental principles of American justice.

Perhaps most importantly, the La Placita Raid reminds us that immigration policy affects real people—families, children, and communities with deep roots in American soil. The human cost of enforcement actions extends far beyond statistics and policy debates.

Legacy and Remembrance

In 2025, La Placita Park remains adjacent to Olvera Street in Los Angeles, although few visitors are aware of its dark history. The events of 26 February 1931, have been largely forgotten in mainstream American historical narratives despite their profound impact on Mexican-American communities.

Through the years, local historians and community activists have worked hard to bring this history to light. Through websites, social media posts, and articles (like this one), they've put a spotlight on what transpired that day in the hope of ensuring not only that the stories of those affected are not lost but also that history will not repeat itself.

In 2005, California enacted the "Apology Act for the 1930s Mexican Repatriation Program," which formally recognized the harm done to Mexican Americans and Mexican nationals who were forcibly removed, pressured, or coerced to leave the United States during the 1930s. This act acknowledges the injustices of the Mexican Repatriation period, though comprehensive federal recognition remains elusive. Other states like Texas, Indiana, and Illinois and the Federal Government have not made any attempt to formally recognize their participation in the Mexican Repatriation.

The La Placita Raid and Mexican Repatriation stand as a reminder of what can happen when fear overcomes compassion. It reminds us that when economic anxiety is directed at our vulnerable communities and when the machinery of government is turned against its own people, we, the people of the United States of America, all lose.

Conclusion: Why This History Matters

When you research your family history, you not only uncover how major historical events may have directly shaped your ancestors' lives, but you also gain insight into the broader, indirect impact those events had on communities and society as a whole. Moments such as the La Placita Raid highlight the importance of understanding history in its entirety, not just the aspects that evoke comfort and warm feelings. Recognizing the full scope of historical events is essential not only to honor those who suffered on 26 February 1931 but also to prevent the recurrence of events like the Mexican Repatriation.

The families who gathered at La Placita Park that day were Angelenos and Americans. They were neighbors and friends who contributed to their communities and helped make this city the big, bold gem that I, and so many others, love.

Remembering their story is not just an act of historical preservation, but a call to safeguard the values of justice, equality, and compassion that define our shared American identity.

I’ve lived in Los Angeles for fourteen years. It is a city I love deeply and with all my heart. When I see images of Los Angeles on television shows, in films, or in still photography, my breath catches in my throat, and my heart skips a beat – that is how much I love this city.

My love only grows deeper with each passing year, which is why I decided to write this bonus post about the 1931 La Placita Raid.

For those researching their Mexican and Immigrant heritage, here are some places to look:

Resources:

The National Archives: The National Archives holds a vast collection of federal records, including those related to immigration and naturalization. While repatriation may not be explicitly documented, you might find evidence of departures or border crossing during this period. Items like the Immigration and Naturalization Records are a good place to start.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS): Formerly the the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), the USCIS offers fee-for-service genealogy program. They can assist you in finding official records and tell you how to access them. This site is useful if you are seeking dual citizenship in other countries, as well as to help you learn more about your immigrant family history.

County Archives: It’s easy to fall into the trap of only searching online, but local (to you or in the area your ancestor lived) county archives often hold records related to welfare programs, public health, and social services. Each of these may provide clues about your family’s situation during the Great Depression. Sites like FamilySearch, or the Society of American Archivists, offer lists of local archives.

Historical or Genealogical Societies: Local societies have may have collections of materials including oral histories, newspaper articles, and photographs. Sites like Cyndi’s List, FamilySearch, and USGenWeb Project offer useful lists that can lead to you societies local to you.

Mexican Genealogy: This site offers a host of resources to help you learn more about your Mexican Heritage. Set up like Cyndi’s List or USGenWeb — it is designed to help you find the resources you need to learn more about your Mexican Heritage.

Los Angeles Historical Society: to learn more about the history of Los Angeles.

Southern California Genealogical Society: to locate genealogical resources about people in and from southern California.

“The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived, and dishonest—but the myth—persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.”

— John F. Kennedy

To learn more about Genealogy by Aryn - head over to GenealogybyAryn.com, stop by and say hello on Bluesky - Instagram - Facebook - YouTube

Be sure to check out my Etsy Shop and stop by my Genealogy Shop.

Looking to learn more about writing your family history? Check out From Research to Novel!

For more information about my Genealogical Services visit GenealogyByAryn.com or email me at aryn.genealogy@gmail.com. For more information on Writing Services - visit ASYounglesAuthor.com

You made it to the very end!! THANK YOU!! Don’t forget to give this post a heart and a restack. Both help to make Genealogy by Aryn visible on Substack.