Picture this: two rough-hewn Kentucky prospectors walk into a San Francisco bank, their dusty clothes tell the bankers one story, but those same garments also concealed a fortune in raw diamonds and rubies.

At first, they're reluctant to speak. Finally, they show their glimmering assets and state they need the gems appraised before revealing the secret location of their mine. You know, the one where they unearthed every single last precious gem they had on their persons.

The bank happily obliged, and then, once the appraisal happened, word began to spread.

Within months, some of America's wealthiest men, including Edward S. Rapallo, Baron von Rothschild’s American Representative and the founder of Tiffany & Co., Charles Tiffany himself, poured millions into the discovery of the century. Because, as we all know, when you have a fortune of money, the one thing you want (or plainly need) more of is MORE money – and these two unrefined Kentuckians, Philip Arnold and John Slack, were exactly the men who could help them attain it.

There was just one problem. The mine. The gems. The money… It was all a lie.

In an era filled with overnight millionaires drunk on westward expansion and becoming the next big gem tycoon, two cunning swindlers nearly pulled off the perfect crime, that is, until a brilliant geologist decided to look a little too closely at their treasure trove of precious stones.

Today, let's talk about the Great Diamond Hoax of 1872. One of history's most audacious confidence schemes. It is a tale that reads like a sure-fire summer beach read that everyone is talking about, but, in reality, it was a real-life scheme that fooled some of the sharpest minds of the Gilded Age.

Meet the Con Men: Philip Arnold and John Slack’s Cunning Plan

Philip Arnold and John Slack were hardly the men you'd expect to orchestrate a million-dollar fraud like the Diamond Hoax of 1872, which is probably why they were initially so successful. Arnold, a former Confederate soldier turned prospector, had spent years chasing gold in California with little success. Slack, his cousin and partner, was a small-time miner with big dreams and empty pockets.

But what they lacked in refinement, they made up for in cunning.

While the duo, like so many other prospectors, weren’t making enough to cover more than their expenses, they used their time in the mountains to learn something other than finding their riches in hills. They learned that people believe what they want to believe, especially when enormous profits are at stake. Living through the post-Civil War boom, they knew that America was hungry for the next great mineral discovery.

Gold had built California.

Silver was transforming Nevada.

Why not propose the ideas of diamonds hidden in the unexplored territories of the American West?

With this idea in mind, in early 1872, the pair traveled to London and Amsterdam, where they purchased rough diamonds and other precious stones worth about $35,000, (over $922,000 today) as a calculated investment. They were careful to choose uncut gems that would appear naturally occurring, and avoided polished stones at all costs, because they might arouse suspicion.

That is how it all began.

Salting the Mine: How Rough Gems Fooled the Richest Investors

Arnold and Slack selected their pitch carefully. It was a remote mesa in northwestern Colorado, near the Wyoming border. It was the perfect location because it was isolated enough to discourage casual inspection, yet accessible enough for potential investors to visit.

Like any magician, this was their stage, where they would perform their masterpiece of deception.

Working under the cover of darkness, the two men "salted" the land with their purchased gems. They pressed diamonds into cracks in rocks, scattered rubies across the ground. They even fired gems from shotguns into cliff faces to create the appearance of natural deposits. The process was painstaking and theatrical, designed to fool even experienced miners who might examine the site. In the end, the salting was so convincing that gems appeared to occur naturally in the rock formations, embedded just deep enough to suggest vast deposits below.

As they painted the mountainside with the gems they brought back from Europe, they must have been thinking that if their scheme worked, they would be richer than we ever dreamed.

Fooling the Elite: Diamonds, Banks, and the Rothschild Connection

The con began in earnest when Philip Arnold and John Slack arrived at the Bank of California in San Francisco, carrying a leather bag filled with raw diamonds. They claimed to be simple prospectors who had stumbled upon an incredible discovery but needed expert appraisal. Their story was that until they knew exactly what they had discovered, there was no way they would share the news with anyone.

This apparent reluctance to discuss details only heightened interest.

Once the diamonds were assessed, word quickly spread through San Francisco's financial circles. George D. Roberts, a mining executive described as a prominent businessman by local newspapers, became their first major mark. Just like the bank, they showed up disheveled dressed and a little worn for wear, but also carrying a small sack of uncut diamonds. Soon, George D. Roberts and his pattern, Ashbury Harpending, a San Francisco financier and mining promoter, gave Arnold and Slack money to further their expedition in the same area they found the first batch of diamonds.

Soon, the scheme attracted even bigger fish, like Edward S. Rapallo, Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild's American representative who was in charge of all investments and business matters for the Rothschild family in the United States. Rapallo never actually invested in the faux diamond field, but with his name attached to Arnold and Slack’s scheme, it brought prestige and legitimacy to their scam. Later the diamonds were brought to Charles Lewis Tiffany, the cofounder of Tiffany Co., where he mistakenly assessed them at $150,000, which far exceeded their actual worth.

With the combination of the Rothschild name and the inaccurate assessment from Tiffany, Arnold and Slack were able to ease the skepticism of potential investors.

People like William Ralston, the president of the Bank of California, William C. Lent a San Francisco mining entrepreneur, General George S. Dodge a financier, and Henry Janin who was not an initial investor but purchased stock later in the game.

Together, the credibility and reputation of these men helped Arnold and Slack raise more than $600,000, over 15 million dollars today, before their fraud was discovered.

Clarence King’s Skepticism: The Geologist Who Cracked the Scam

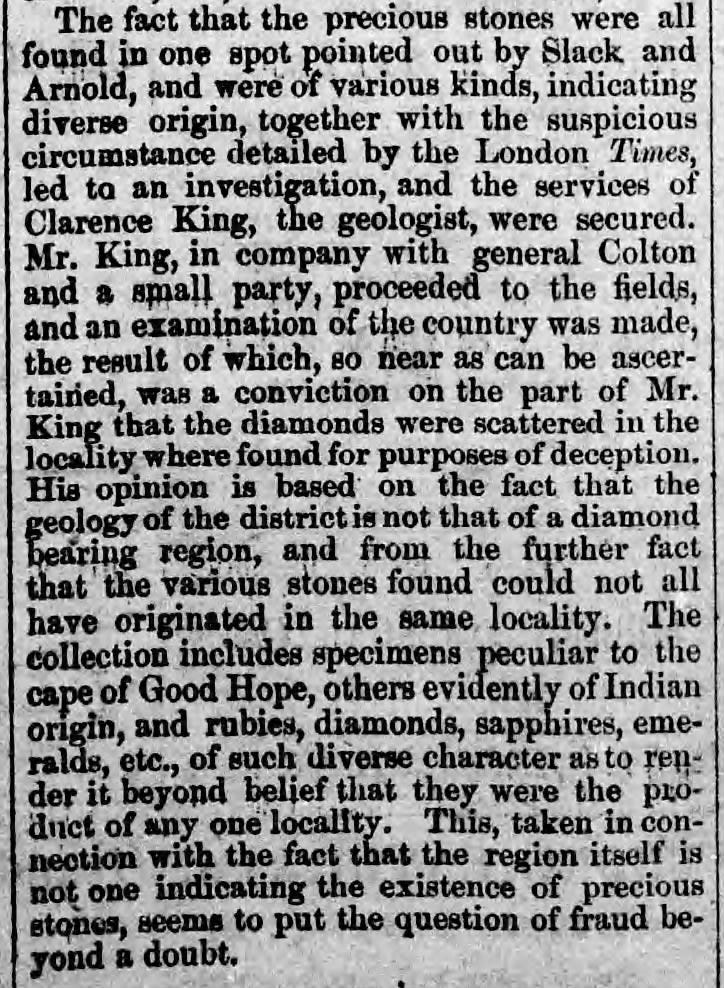

While most of America's elite was blinded by diamond fever, one man remained suspicious. Clarence King, a brilliant geologist who, along with his team of fellow geologists Samuel Emmons and cartographer A.D. Wilson found the discovery a bit fishy. They had spent time in that region surveying the area as part of a U.S. Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel – a major government survey of the Western United States and never found any evidence of diamonds in that region.

had spent years surveying the American West, found the whole affair fishy. King had explored vast stretches of the western territories and knew their geological formations intimately.

King's suspicions were aroused by several factors: the convenient proximity of different types of gems in one location, the surface distribution of the stones, and the overall geological impossibility of the site. Against considerable pressure from investors who wanted to believe, King organized his own expedition to examine the claims.

The Exposure: How the Great Diamond Hoax Was Unraveled

In November 1872, King and his team confirmed his worst fears. The distribution of gems was entirely unnatural – no geological process could have created such a convenient surface scatter of valuable stones. More damning still, King discovered that many of the diamonds exhibited tool marks, indicating recent human handling.

The geologist's investigation revealed the fraud's fatal flaw – Arnold and Slack had been too generous with their salting. Real diamond deposits don't conveniently place gems on the surface for easy collection. The very abundance that made the site seem so valuable was precisely what proved it fake.

Aftermath and Fallout: Consequences for Arnold, Slack, and their Victims

The exposure of the hoax had far-reaching consequences. Philip Arnold, the mastermind, initially escaped prosecution and retired to his Kentucky farm. However, he couldn't escape the controversy entirely. In 1878, he was shot and killed during a dispute over property, some say by an investor who had lost money in the scheme.

John Slack disappeared into obscurity, taking his share of the profits with him. Unlike his partner, he managed to avoid both prosecution and violent retribution, living out his days in anonymity.

The victims of the hoax faced not only financial ruin but public humiliation. Many of America's most respected businessmen had to admit they'd been duped by two uneducated prospectors. The scandal highlighted the dangerous intersection of greed and gullibility, even among the supposedly sophisticated.

Clarence King emerged as the hero of the affair, his reputation as a scientist and integrity intact. His methodical approach to investigating the claims became a model for future fraud investigations. Congress later awarded him a special commendation for his service to the nation.

Diamond Fever and Investment Mania: Historical Parallels and Modern Warnings

The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872 echoes earlier moments in American history, like the California Gold Rush, which encapsulates a familiar cycle of speculative fever and the pursuit of instant riches. News of the supposed diamond discovery in the West set off a frenzy reminiscent of the gold rush twenty-four years earlier – sending prospectors, speculators, and even seasoned financiers scrambling to stake their claims on the next big low investment, high reaping rewards.

In both cases, rational caution was often abandoned as a combination of greed and optimism swept through even the most reputable circles, making accomplished businessmen susceptible to schemes that promised boundless profit, and tricking poorer citizens into thinking it would be their ticket out of poverty.

While the Gold Rush created boomtowns and reshaped the landscape, the diamond hoax ignited a brief but intense “diamond fever,” with people across the West chasing rumors and investing in hope of striking it rich. Both episodes are part of a larger American tradition of manias and bubbles that can be seen throughout the history of the country. From land speculation in the early Republic to later oil booms and stock market frenzies, all propelled by the allure of easy wealth.

Lessons from the Diamond Hoax: Greed, Gullibility, and the American Dream

This enduring pattern, underscored by colorful characters and wild rumors, reveals how deeply the dream of sudden fortune and the susceptibility to hucksterism are woven into the fabric of the nation’s history. The pattern also shows the launching point for Arnold and Slack's initial scam – they had seen it happen before, why not help it to happen again and line their pockets while doing it.

Would you have believed the diamond discovery? Share your thoughts or favorite historical hoaxes in the comments below! For more tales of true historical intrigue, subscribe to my newsletter and never miss a story of human ambition, deception, and the pursuit of fortune.

Resources:

Open Educational & Archival Resources

The Gilded and the Gritty: America, 1870–1912

An open educational resource with annotated primary sources, period documents, artwork, and literary texts. Organized by themes like progress, memory, and cultural identity, it helps readers explore the social, economic, and political forces of the Gilded Age, and includes discussion questions for further reflection.Digital History: The Gilded Age

Offers a comprehensive narrative overview, thematic essays, timelines, and primary sources about the 1870s–1900. It covers westward expansion, mining booms, railroad building, labor unrest, immigration, and everyday life—critical context for understanding the world your ancestors navigated.Chronicling America (Library of Congress)

Search US newspapers published between 1789 and 1963. Find contemporary reports on mining booms, scandals, immigration, politics, and even specific names or places—ideal for understanding “what was in the news” during your ancestors’ time.Primary Source Guides—Gilded Age/Progressive Era

University and library guides (e.g., Lone Star College’s Primary Sources History page) compile links to digitized newspapers, photographs, magazines, letters, and government documents from the era. These collections help you find stories and perspectives from everyday people as well as from powerful figures.

Digital Collections & Databases

The Gilded Age and Progressive Era Digital Collections

Many major libraries and universities host digital archives with business records, personal papers, political cartoons, photographs, and ephemera from this period. Start with your local university’s history library guides, which often curate free-access collections for public use.National Humanities Center—Gilded and the Gritty

Free, thematic primary source compilations with scholarly annotations. Includes sections on cultural memory, social progress, and the lived reality of various groups including immigrants, women, and minorities.

For Historical Context and Storytelling

Wikipedia: Gilded Age

Provides a reliable overview and background on the economic, social, and political dynamics of the era, along with suggestions for further reading.Britannica: Gilded Age

A concise introduction to the period’s major trends—industrialization, wealth inequality, corruption, urbanization—that shaped the context for events like the diamond hoax.

Research Tips for Readers:

Use these resources to find not just names or dates, but the stories and social context behind your ancestors’ lives: newspaper mentions, community events, economic booms/busts, and cultural changes.

Cross-reference what you find in genealogy databases with period newspapers or local digital archives—what were your ancestors likely seeing, hearing, or reacting to?

To learn more about Genealogy by Aryn - head over to GenealogybyAryn.com, stop by and say hello on Bluesky - Instagram - Facebook - YouTube

Be sure to check out my Etsy Shop and stop by my Genealogy Shop.

Looking to learn more about writing your family history? Check out From Research to Novel!

For more information about my Genealogical Services visit GenealogyByAryn.com or email me at aryn.genealogy@gmail.com. For more information on Writing Services - visit ASYounglesAuthor.com

Thanks for sticking around—hope you enjoyed the ride through history as much as I did sharing it!

What a fun story!

What a great story Aryn, and so well told. I love it! Just shows there is no end to greed for the wealthy, and more than enough is never enough,. I couldn't help feeling disappointed that the con didn't work.