Close to where I live is a park called Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area. It was named after a former member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors who worked diligently to transform the area from the former Inglewood Oil Fields into the park it is today.

Through the years, the area has been home to many events in Los Angeles – from part of the 1932 Olympic Village, which was built in Baldwin Hills, and a section of what is now Kenneth Hahn State Park,

To begin the backdrop in Dr. Dre’s 1993 music video for Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang. Take note at 1:13 into the video:

These days, it is a welcome open space in a very large, very populated city. One I’ve used many times for morning jogs, family time, and to simply enjoy nature. Visiting Kenneth Hahn for a midday excursion is how I first learned about the Baldwin Hills Reservoir.

Years ago, when my child was still in preschool, we visited Kenneth Hahn Park. There, as our kids played together, I struck up a conversation with a grandfatherly man—let’s call him “Grandpa.” What began as small talk soon turned into a history lesson I’ll never forget.

He said, “I used to work here.”

“At the park?” I asked, not really knowing anything about the park other than it was, well, a park.

“No,” he said with a soft chuckle. “At the Reservoir.”

He gave me a quick rundown. The area used to be an oil field, but in the 1950s, the city built a Reservoir. The area is high up in the park, a short drive from where we were sitting. It was, and still is, known as “the bowl.” A place I enjoyed with my son, full of trees to climb, shady spots to rest, and flowers to admire.

But once upon a time, the Bowl had been the Baldwin Hills Reservoir.

This was the story he told me. He worked at the Reservoir. Part of the staff that ensured things were on schedule and working well. Throughout the years he worked there, the day he remembered most was December 14, 1963. He had worked the night shift, clocking in on the 13th, and the next day, when his shift was done, he got into his car and drove home.

The town was decked out with Christmas decorations, and the air was cool and crisp. He knew his family would be home and just starting their day when he arrived, but all he could think about was going to bed.

They knew he would need sleep. With the holidays coming up, there were school events, family gatherings, and Christmas parties, so they always gave him space.

It was past midday when he got home, so he ate and spent time with his wife, but he was still tired. He crawled into bed. He couldn’t remember the exact time, but what he did remember was that, as he finally fell asleep, his phone rang.

You have to remember, in 1963, a ringing rotary phone could jolt anyone awake.

He said to me, “I pulled myself out of that bed, yanked the phone off the wall, and before I could say a word, I heard – the dam broke. You have to come back in.”

And he did.

The dam broke at 3:38 pm on a seemingly ordinary Saturday afternoon. Like the man I met at Kenneth Hahn Park, other residents of Baldwin Hills and Culver City were going about their weekend routines—shopping, visiting neighbors, and enjoying the cooler December Los Angeles weather.

Then, as if out of nowhere, 250 million gallons of water rushed down the sides of the Baldwin Hills, literally washing away any sense of normalcy.

I don’t know what happened to the grandfather or his granddaughter. I never saw them at the park again, but his story remained etched in my mind.

History of the Baldwin Hills Reservoir

The Baldwin Hills Reservoir was constructed between 1947 and 1951 as part of Los Angeles's growing water infrastructure. Perched on a hill overlooking the affluent Baldwin Hills neighborhood, the massive concrete structure held 250 million gallons of water—enough to supply the surrounding communities during peak demand periods and emergencies. LA is known for its dry climate, so the reservoir was one way to combat the drought conditions and secure drinkable water for areas surrounding the Baldwin Hills.

The reservoir was an engineering marvel of its time, boasting a distinctive design with sloping concrete walls that rose 65 feet above the surrounding terrain. From the outside, it appeared to be a modernist fortress, a symbol of post-war American engineering prowess. Inside, it held enough water to fill about 380 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The location seemed ideal: elevated terrain provided natural pressure for water distribution, and the growing post-war communities below desperately needed reliable water storage. What planners knew about but dismissed was how the very ground beneath the reservoir would ultimately seal its fate.

Before the Reservoir

At one time, the Inglewood Oil Fields were located on top of the Baldwin Hills. The very fields Kenneth Hahn fought to have removed. In its heyday, the Inglewood Oil Fields was one of the most productive oil extraction sites in California, which is why part of it still operates today.

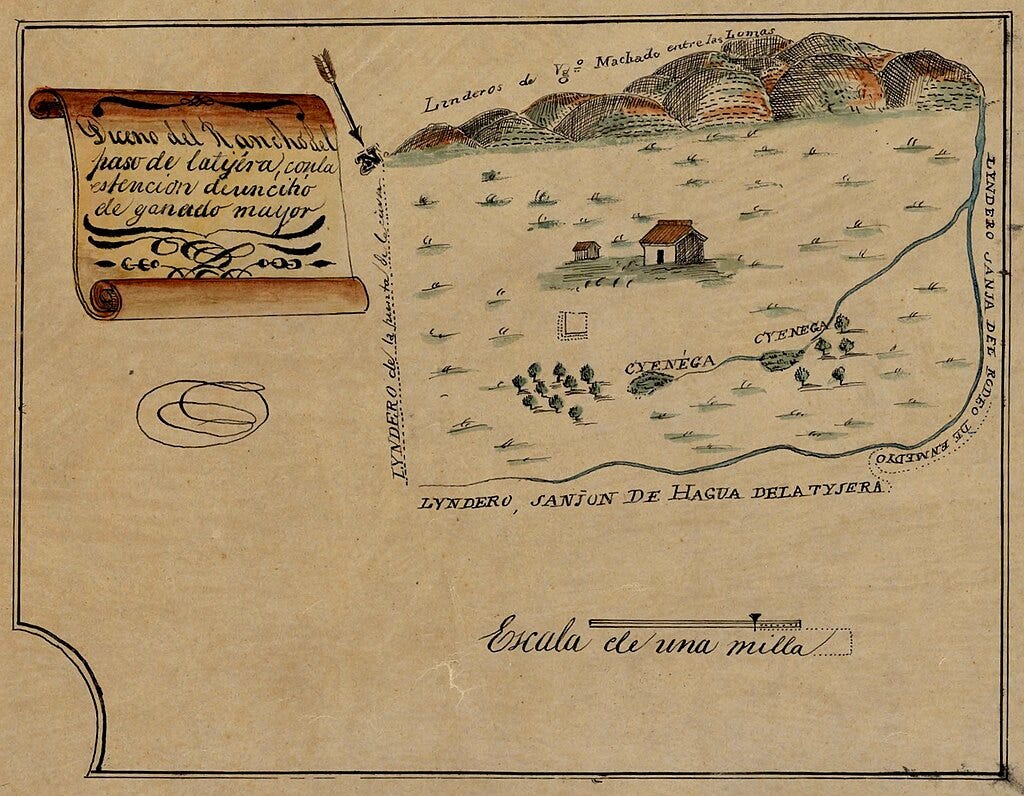

Before the 1900s Oil Boom, the area was used for farming and known as the Rancho La Cienega o Paso de la Tijera. A ranch whose name was immortalized in street names – La Cienega (the swamp) and La Tijera (the scissors). Before that, it was the home of the Tongva people, the original inhabitants of the Los Angeles area.

Then, in 1924, oil was found in the Baldwin Hills. Standard Oil (now Chevron) began drilling and extracting millions of barrels of crude oil from beneath the area. By the 1960s, this intensive extraction had created a hidden network of cavities and weakened substrata beneath the neighborhood.

This Oil extraction caused something known as subsidence, or the gradual sinking of land as underground spaces are emptied. While this process typically occurs slowly over decades, it can create stress fractures, fault lines, and instability in structures built above.

The Baldwin Hills Reservoir’s massive weight, combined with a compromised foundation, made disaster almost inevitable.

Also, in hindsight, geologists later determined the combination of oil extraction, natural fault lines, and the immense hydraulic pressure from 250 million gallons of water sitting inside the concrete dam created the perfect conditions for catastrophic failure.

What the surveyors in 1947 thought was the perfect place for a reservoir essentially turned out to be a geological time bomb.

December 14, 1963: The Day Everything Changed

While my conversation with Grandpa took place years ago, the timeline used for this article is based on my research into the events of December 14, 1963.

According to what I’ve learned in the last ten years, the morning of December 14, 1963, looked like this:

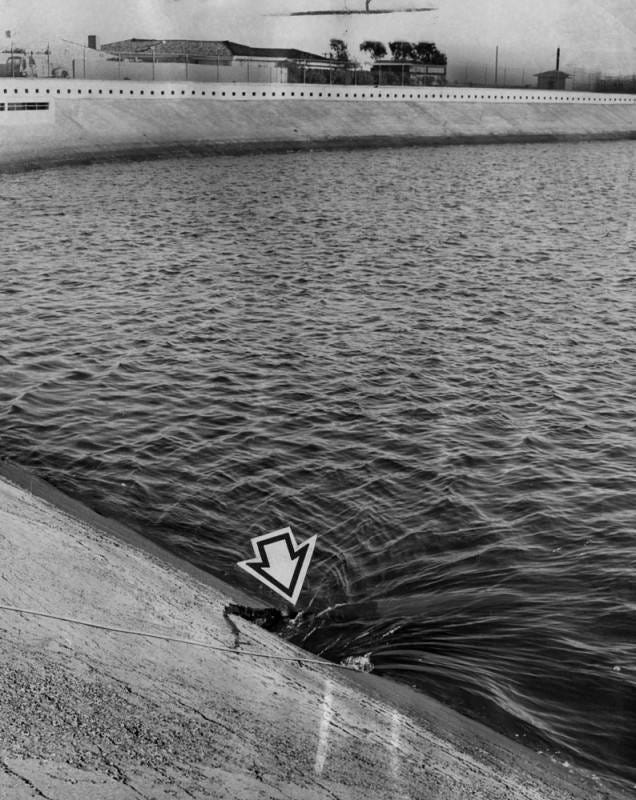

At approximately 11:15 AM on that Saturday morning, after my park friend left his job, residents near the reservoir began to notice water seeping from the base of the reservoir’s structure.

Then, those small leaks quickly escalated to a point where water was actively running.

By early afternoon, the seepage transformed into visible streams.

Not surprisingly, concerned citizens called the Department of Water and Power, but it was a Saturday, and their response was slower than it should have been. Yes, engineers were dispatched to investigate, but the situation was deteriorating faster than anyone realized.

Finally, at 3:38 PM, the unthinkable happened.

A massive section of the reservoir's wall simply gave way. In an instant, millions of gallons of water burst forth in a torrential flood that would forever scar the Baldwin Hills community.

The Wall of Water

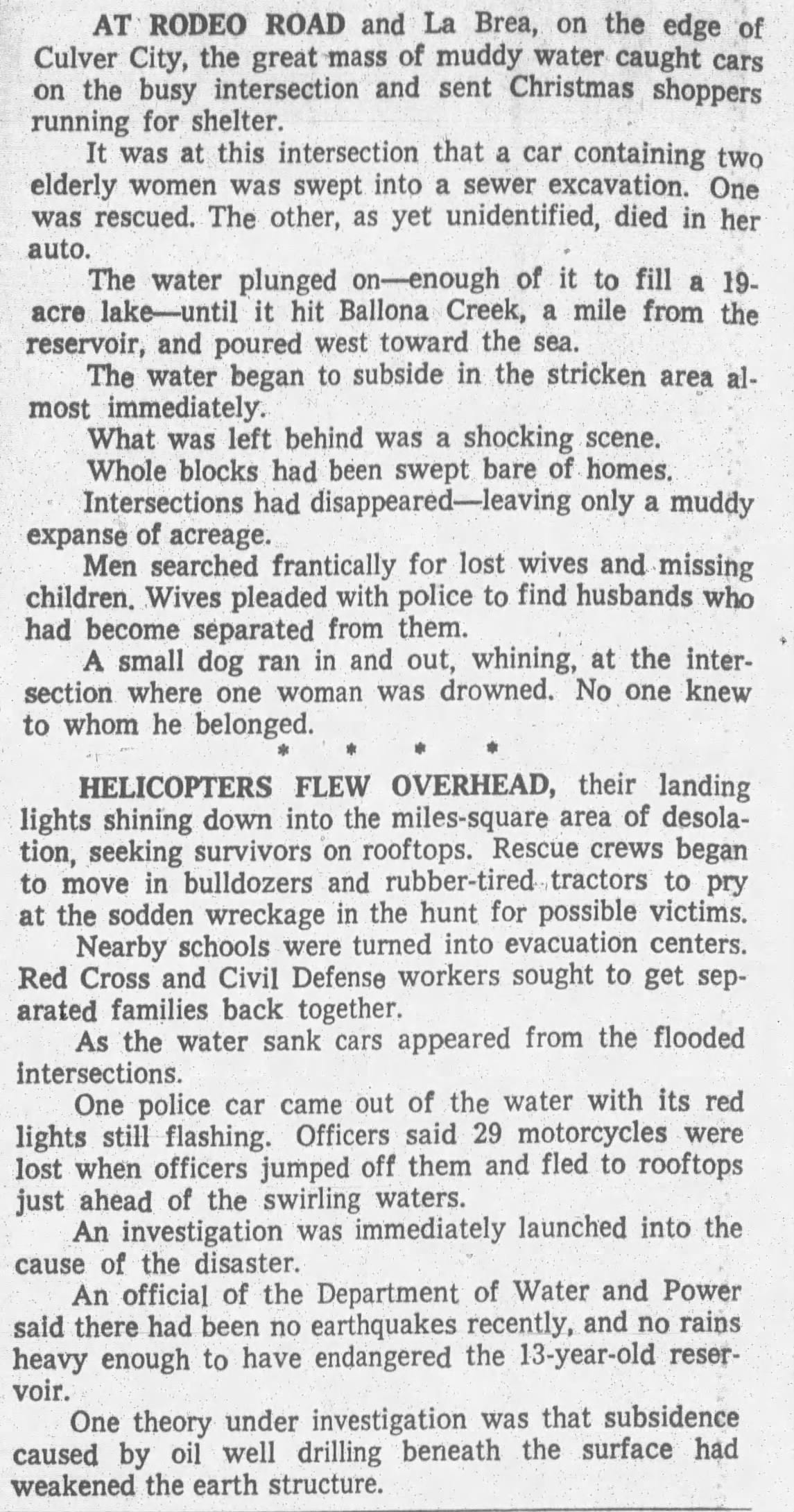

Witnesses described a scene of almost biblical proportions. A wall of water, thirty feet high, came roaring down the hillside, carrying with it chunks of concrete, debris, and everything in its path. The sound was deafening—like thunder mixed with giant and angry ocean waves that wouldn't stop coming.

The flood raced through residential streets at speeds reaching fifteen miles per hour, turning peaceful neighborhoods into raging rivers. Homes that had stood for decades were lifted off their foundations and carried away like children's toys dropped in a stream. Cars were tossed aside or buried under tons of mud and debris.

As seen in this footage take by local news affiliate KTLA:

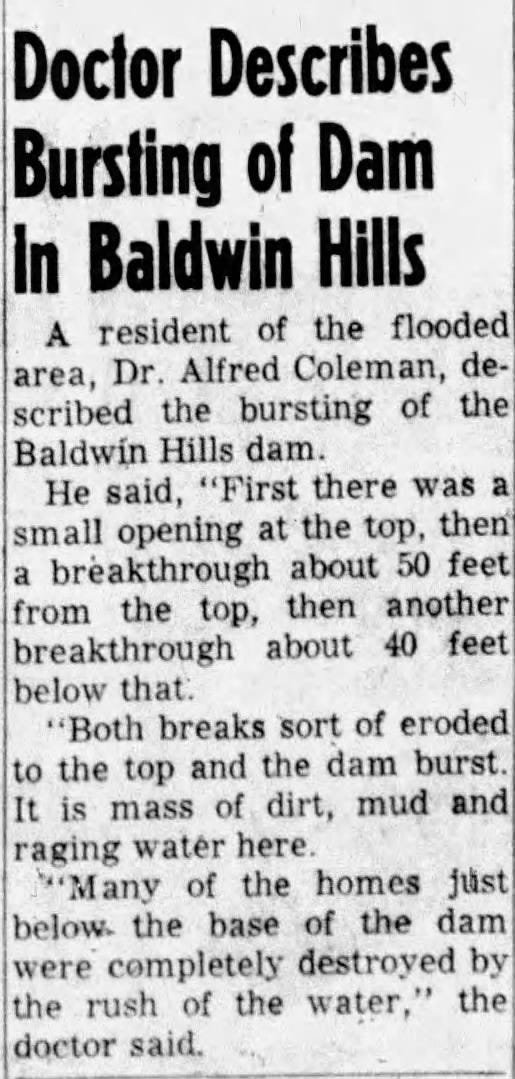

In the Van Nuyn s News and Valley Green Sheet’s December 15th paper, Dr. Alfred Coleman, “...describe the bursting of the Baldwin Hills Dam. He said, “First there was a small opening at the top, then a breakthrough about 50 feet from the top, then another breakthrough about 40 feet below that.

“Both breaks sort of eroded to the top and the dam burst. It is mass of dirt, mud and raging water here.

“Many of the homes just below the base of the dam were completely destroyed by the rust of water.”

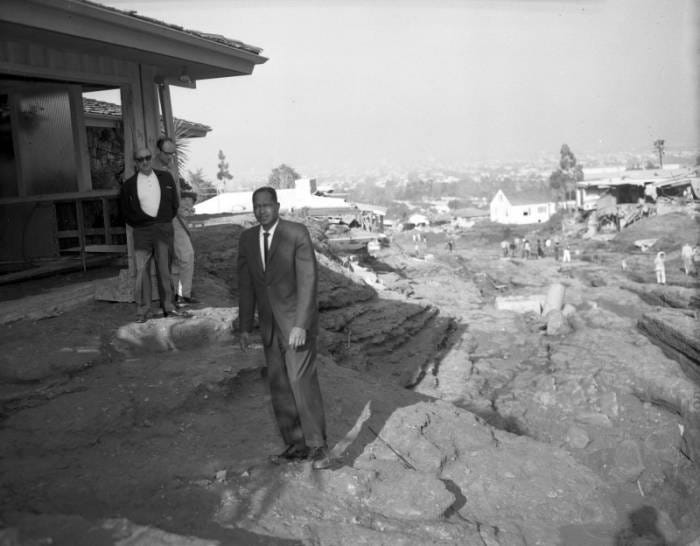

The flood carved a violent path nearly two miles long and up to 1,000 feet wide, leaving devastation that would take years to repair fully.

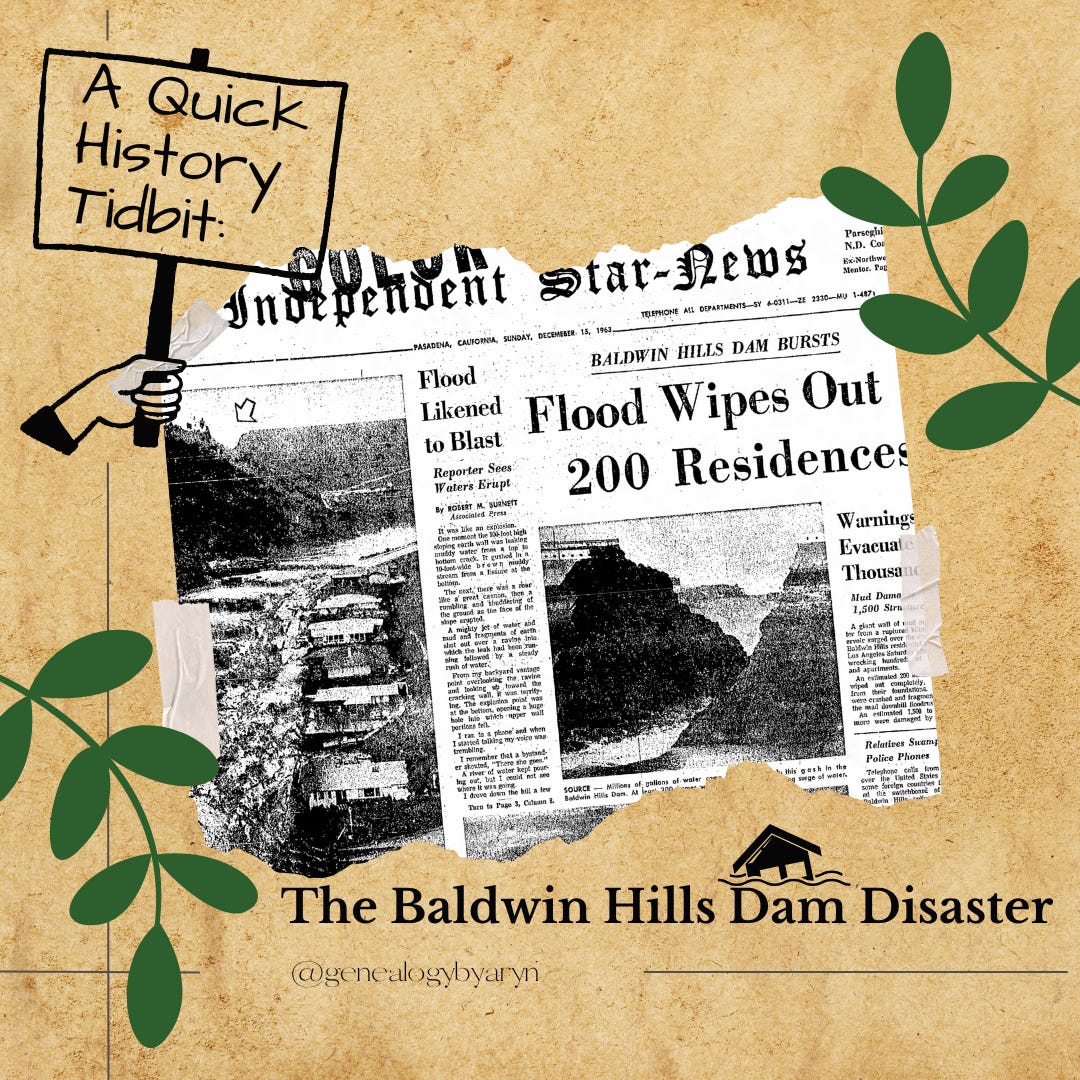

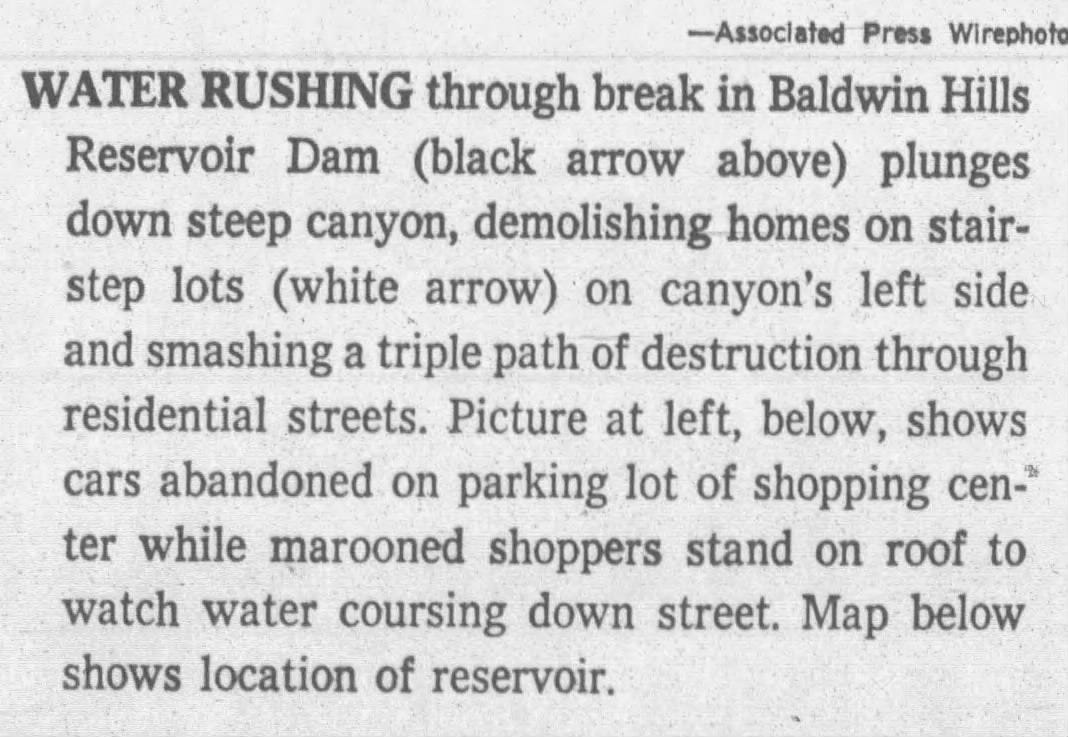

News articles were filled with images of destruction and chaos:

Heartbreak

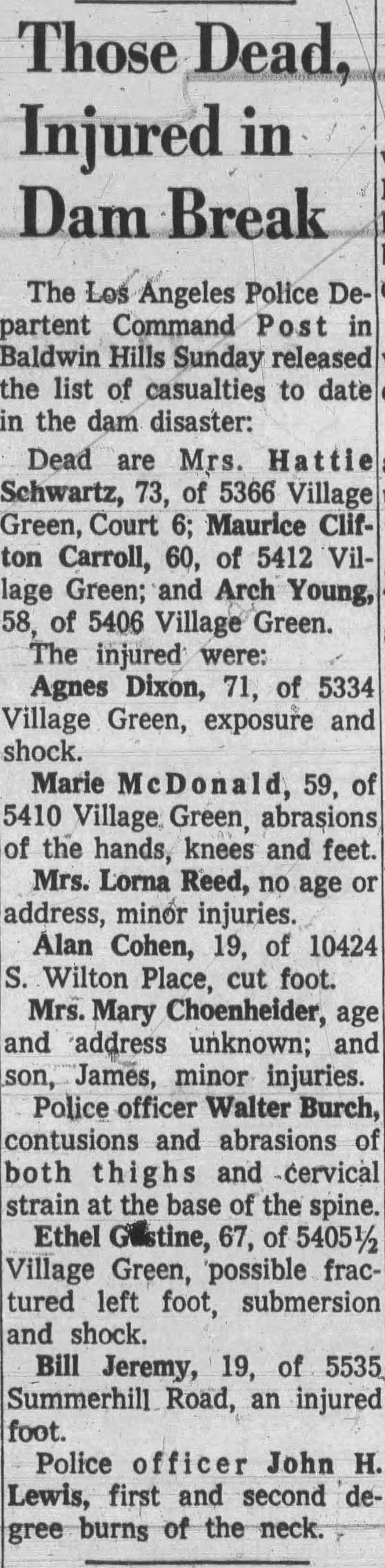

In the end, five people ended up losing their lives that day:

Hattie Schwartz

Maurice Clifton Carroll

Arch Young

Orra G. Strathearn and Archie V. MacDonald

The Aftermath: Counting the Cost

When the water finally receded, the scope of the disaster became clear. The numbers were staggering:

5 people killed

277 homes were destroyed or severely damaged

16 businesses demolished

$12 million in property damage (equivalent to about $120 million today)

Approximately 1,000 people were displaced from their homes

Entire blocks looked like war zones. Where family homes had stood for years, only concrete foundations remained, surrounded by mud and debris. The carefully manicured lawns and tree-lined streets of Baldwin Hills had been replaced by a devastated landscape.

The Red Cross set up emergency shelters for displaced residents, many of whom had lost everything they owned. Insurance battles would drag on for years, as many policies didn't adequately cover flood damage—especially from a reservoir failure.

The Baldwin Hills Reservoir disaster was more than a local tragedy, it was a wake-up call. Engineers, city planners, and the entire Los Angeles community came together to rethink how progress would be shaped from then on. The dam catastrophe prompted sweeping changes in safety regulations, stricter geological surveys, and a new awareness of the risks posed by building atop unstable ground damaged by years of oil extraction and refinement.

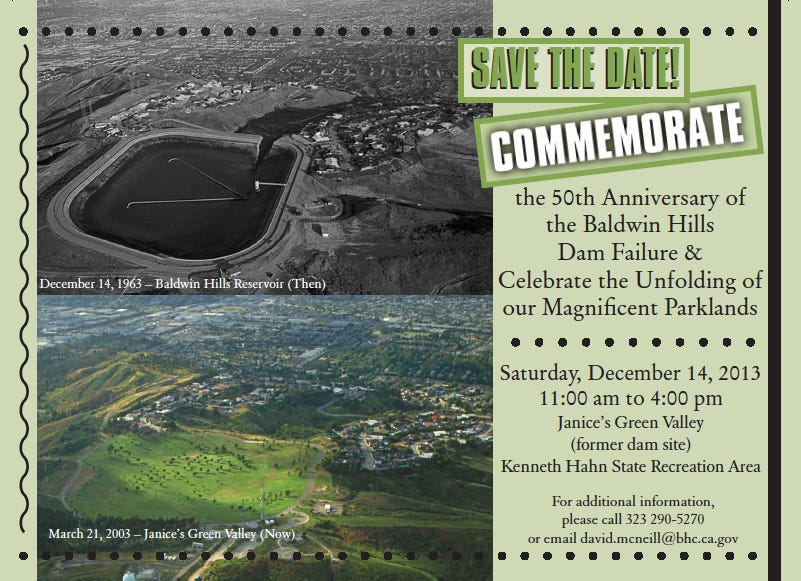

Today, Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area stands as both a memorial and a symbol of renewal. Where a wall of water once tore through homes and lives, children now play, families picnic and joggers trace the path along what was once a literal fault line in the city’s history, circling the Bowl that once held the Baldwin Hill Reservoir.

Whenever I drive by Kenneth Hahn, I think of “Grandpa” and the story he shared with me while his granddaughter and my son played. With family history in mind, echoes of that day in 1963 live on to remind us that beneath the surface of even the most peaceful places, there are stories—of resilience, of loss, and of the lessons we carry forward.

On December 14, 2013, fifty years after the fatal event, a memorial ceremony was held to commemorate the damage, destruction, and loss that occurred that day. The people gathered to remember that while the earth may have opened up that December afternoon, in the decades since, the community has filled that space with remembrance, growth, and hope for the future.

RESOURCES

Newspapers and Periodicals

Local and national newspapers often reported disasters in detail, including lists of victims, survivors, and eyewitness accounts. Digital archives such as Newspapers.com, Chronicling America, and Google News Archive are valuable for searching by location, date, or name.

Disaster-Specific Databases and Websites

Family History Daily Disaster Guide: Offers tips and links to disaster-specific resources for genealogists.

Government and Archival Records

National Archives: Holds disaster-related records, including relief agency files, FEMA records (for modern disasters), and census records that can help identify affected individuals.

Local Archives and Courthouses: May have disaster relief applications, property damage claims, and death or injury records. No link for this one! Look in the area you are researching!

Community Histories and Local Histories

Books, pamphlets, and commemorative publications about local disasters often include names and stories of those affected.

Church Records

Parish registers may list burials or memorials for disaster victims, especially in close-knit communities.

Family Bibles and Personal Papers

Handwritten records, letters, or diaries sometimes mention family members’ experiences with disasters. These are harder to find, but when you do, their worth all the effort.

Reconstructed Records

After disasters, governments sometimes reconstructed vital records. Look for delayed birth, marriage, or death certificates, affidavits, and other substitute documents.

Oral Histories and Interviews

Speaking with older relatives or community members can uncover family stories about surviving or being involved in disasters.

Additional Tips

Google and Google Books: Search for specific disasters by name, date, or location to find historical accounts and book.

YouTube and Genealogy Podcasts: Channels like Family History Fanatics offer tutorials on finding and using disaster-related records.

Disaster Planning for Genealogists: Guides on protecting your own research from future disasters can also provide insights into how records are preserved or lost.

Thank you for reading!!

In case you missed it:

To learn more about Genealogy by Aryn - head over to GenealogybyAryn.com, stop by and say hello on Bluesky - Instagram - Facebook - YouTube

Be sure to check out my Etsy Shop and stop by my Genealogy Shop.

Looking to learn more about writing your family history? Check out From Research to Novel!

For more information about my Genealogical Services visit GenealogyByAryn.com or email me at aryn.genealogy@gmail.com. For more information on Writing Services - visit ASYounglesAuthor.com

Look at you… making it all the way to the end. Thank you and know I appreciate you!!

If you have a second: